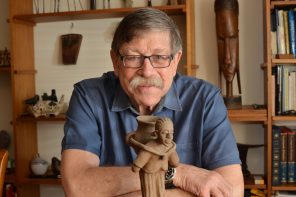

Written by Seymour Topping

During my years as a foreign correspondent for the Associated Press and later The New York Times, I traveled to virtually every region of the world. Among those journeys, the one that remained most vivid in my mind and perhaps most meaningful, happened during the Chinese Civil War between the American-backed Nationalist armies of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong’s Communist forces. I became witness to one of the largest military engagements in history, the outcome of which would profoundly reorder the global balance of power to this day.

My journey began on Dec. 12, 1949. I had learned that more than a million troops were locked in what would become the decisive battle of the civil war near the city of Xuzhou, 75 miles north of Chiang’s capital of Nanking, where I was stationed. So I determined to go behind the Communist lines to interview Mao and report that side of the story.

I packed my duffle with a portable typewriter and drove my jeep to the terminal on the Yangtze River, where a troop train was returning from the front loaded with wounded soldiers. Refugees escaping from the fighting were hanging on to the sides of the train. Old men and women with babies on their backs were perched on top. Nationalist reinforcements quickly boarded. Some soldiers, responding to my entreaties, helped me onto a crowded boxcar. I noticed they were armed with American weapons. A kindly young army officer handed me a bowl of cold rice sprinkled with a piquant sauce. I felt a sense of camaraderie with him, having served myself as an infantry officer in the Pacific theater of World War II.

We spent the night propped against the sacks of rice stashed up the sides of the boxcar to afford some protection from the gunfire of Communist guerrillas waiting in ambush. The steam engine chugged north to the town of Pengpu, near the Huai River on the edge of the vast Huaibei Plain of central China, where the armies were fighting what historically would be recorded as the Battle of the Huaihai. Chinese historians would later compare it with the Battle of Gettysburg, the turning point of the American Civil War. When I arrived in Pengpu, the victorious Communist forces were sweeping south on the plain toward the Huai River.

My plan was to stay in a lonely Jesuit mission until the Communists took Pengpu. I would then emerge and ask to be accepted as the sole Western correspondent covering their advance and request an interview with Mao. I had visited Yenan, Mao’s headquarters, in 1946, was known to the leadership, and hazarded that I would be well-received. I remained in the mission through Christmas, attending the Roman Catholic services conducted in Chinese. Growing impatient, I decided to cross the Huai River on New Year’s Day and hike north to the Communist outposts. I would introduce myself by flashing a photograph taken in Yenan of me posing with senior Chinese officials. At the age of 28, the lure of a great news story obscured thoughts of dangers.

I hired two peasants to carry my bags and crossed the bridge into No Man’s Land, which I had been warned was bandit territory, and began walking along railroad tracks. Nationalist planes droned above on the way to bomb the advancing Communist troops. About five miles out, we ran into a road block manned by four men in peasant garb, who confronted us with submachine guns. As they shouted at me with fingers on triggers, one of my baggage carriers yelled, to my vast relief, “He’s an American correspondent.”

Men in uniform who had been covering the road block from a distance appeared and I knew then I was in the hands of Communist militia. I was taken on a long march through a recent battle zone to a militia headquarters. Decomposed bodies of soldiers still lay in the fields or in trenches picked at by village dogs and ravens. I spent the night in a shed sleeping on bags of grain with my woolen army cap pulled over my face as rats scampered over me.

In the morning, we marched all day to another post. The commander there was friendly. Over a camp fire, he asked me questions about life in the United States and I listened as a commissar lectured the troops, who then sang “On to Nanking.” I was led on horseback all the next day to a headquarters located on the edge of a battlefield where, I later learned, the Nationalist garrison fleeing the key city of Suchow was surrounded by 300,000 Communist troops. I was taken to a peasant hut, put under guard and spent the night listening to the thud of artillery fire. When the firing ceased, I knew the encircled Nationalists had been overrun.

My hope of an interview with Mao was soon shattered. In the late morning, Wu, a deputy commissar who had interrogated me on arrival, entered the hut to tell me, “In regard to your mission, we ask you to return. This is a war zone. It is not convenient for you to proceed.” He did not reveal if my request for an interview had reached Mao. Overriding my questions, he said said, “The horses are waiting.”

My journey between old and modern China ended there. I had been witness to the final phase of the Battle of the Huaihai, in which the Communists eliminated 550,000 Nationalists to their loss of 30,000. It was Chiang’s Waterloo.

As I mounted my horse, Wu came up beside me and said gently, speaking in English for the first time, “I hope to see you again. Peaceful journey.”

The history of the Huai Hai campaign is in Seymour Topping’s recent memoir “On the Front Lines of the Cold War, An American Correspondent’s Journal From the Chinese Civil War to the Cuban Missile Crisis and Vietnam.”

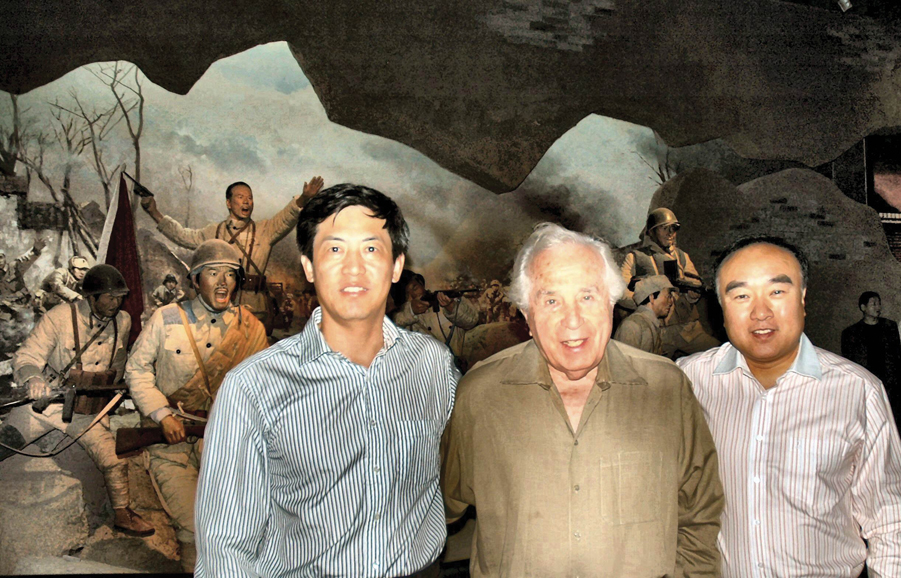

Huaihai, then and now

On the 60th anniversary of the Battle of the Huaihai, I was invited to revisit the battlefield and tour a magnificent museum in Suchow that commemorates the campaign. I was accompanied by my wife, Audrey, a photojournalist I had met in China when she was attending Nanking University, and our daughter, Karen. The museum was crowded with Chinese tourists viewing tableaux of battle scenes and life-sized wax figures of both Communist and Nationalist generals as well as photographs of 20,000 to 30,000 soldiers killed in combat. Huge revolving scenes of the battle had been depicted on canvas that had taken 10 painters eight months to complete. The eager faces of Chinese children watching was proof enough that the battle would not be forgotten. For six nights, Chinese TV showed a six-part documentary of the Huaihai campaign. One of the episodes was devoted to an interview with me, in which I relived my journey from the Jesuit mission to the battlefield.