Written by Seymour Topping

When Fidel Castro recently celebrated his 90th birthday, the frail Cuban leader sat in what seemed to be a specially equipped wheelchair at a televised gala listening to a musical tribute by children and viewing film depicting his revolutionary rise and exercise of power.

It was his first public appearance since April when he spoke at a Communist Party congress cautioning it to adhere to socialist ideals even as the nation was engaging in a process of normalization of relations with the capitalist United States that has been foreshadowed by cultural tourism and exchanges.

On his historic visit to Cuba in March, President Barack Obama was not received by Fidel Castro. He met with his younger brother, Raul, to whom Fidel yielded the presidency in 2006 after he suffered gastrointestinal bleeding.

I have always considered myself fortunate in having had the opportunity to interview Fidel Castro at a time when he was fit physically and not shy of being informal with an American journalist. In November 1983, when I was managing editor of The New York Times, I traveled through South America interviewing leaders and hoping that Castro would respond to my repeated requests for what would be a rare interview. I had been based in Moscow during the Cuban missile crisis and was eager to get Castro’s thoughts about the outcome of his engagement with President John F. Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev.

I was in a hotel bar in Managua, Nicaragua, when I got a call from the Cuban ambassador. The next morning, Times colleague Bill Kovach and I were aboard a Cuban airliner. In Havana we waited two days before I received a phone call in my hotel room at 9:30 p.m.: “We will pick you up in a moment. The president is ready to receive you.”

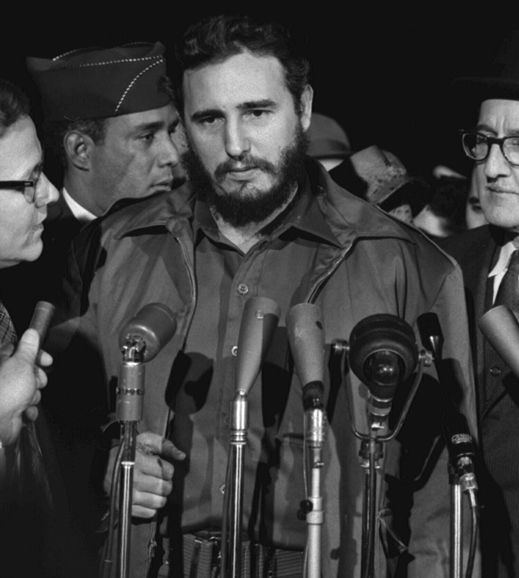

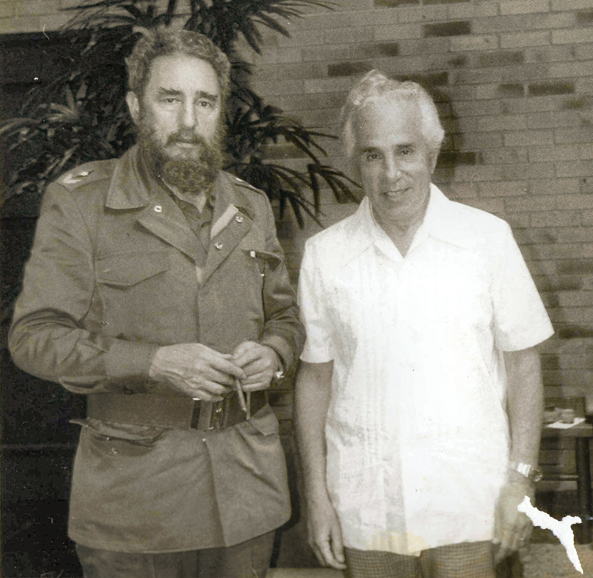

After surrendering our cameras and tape recorders at the Council of State building, we were ushered into Castro’s spacious office, a wood-paneled room lined with bookcases. Castro greeted us as we entered. He was a tall figure, dressed in his familiar uniform — green combat fatigues, a short combat jacket with a leather belt and black zipper boots. His beard was quite long and rather straggly, but his hair with its silver gray streaks was well groomed. He waved us to beige leather couches arranged around a coffee table.

His manner warm and friendly, Castro asked me to sit beside him, saying he would like to be able to look into my face. He apologized for inviting us to his office at such a late hour and added with a smile that possibly we would have preferred to go to the Tropicana, a splashy nightclub. When he invited questions, I asked about his relations with Moscow. He replied that they were on a mutual basis. He was grateful for Moscow’s large-scale economic assistance. He did not complain about his treatment in the resolution of the missile crisis. Indeed, he had made known his resentment that Russian leader Nikita Khrushchev, in negotiating the crisis settlement, had not insisted the U.S. terminate its embargo on trade with Cuba. But, gesturing with hands raised, Castro recalled that when he first took power, he was isolated and under pressure from the United States and didn’t know which way to turn. He said it was the Soviet Union that came forward with the assistance he needed to build and preserve the Cuban nation, and the Cubans could not overlook that fact. He stressed that Cuba retained its independence and that Soviet military advisors were in Cuba solely to train his army.

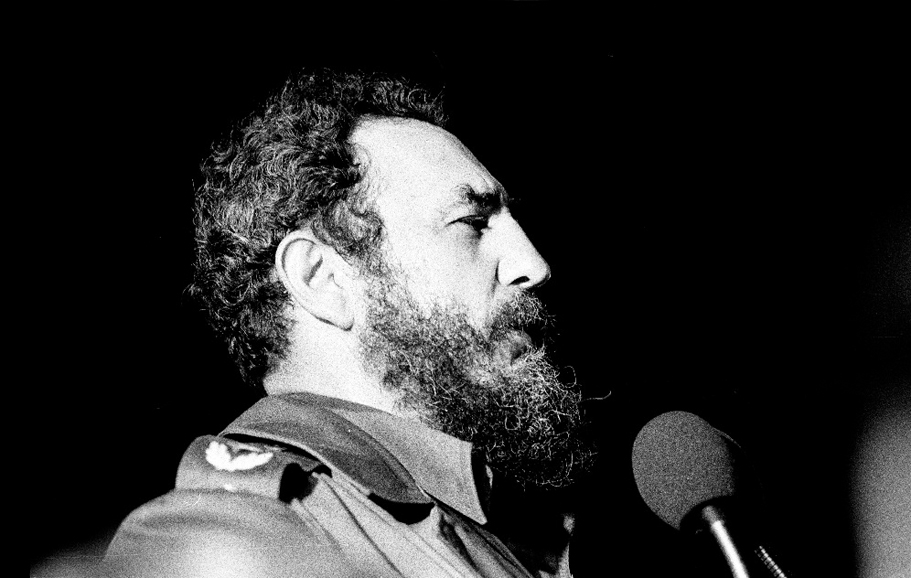

In replying to my questions, Castro stared intently into my eyes and often raised his hands in expressive gestures. His Cuban interpreter translated simultaneously and mimicked Castro’s inflections and expressions. Castro’s remarks revealed a broad knowledge of foreign affairs and history, including that of the United States. He frequently cited names of relevant personalities, dates and statistics. When he spoke tenderly of the work of thousands of Cuban teachers in allied Nicaragua, I thought, what a contrast. This is the same man whose communist regime had so brutally repressed political opponents.

At midnight, after the conversation had continued for more than two hours, I was thanking Castro, when he interrupted to say smiling: “Well, it’s not too late to go to the Tropicana.” A tray of mojitos and daiquiris was brought in. For himself, Castro poured two drinks of Chivas Regal, saying he preferred Scotch to rum. During our meeting, Castro smoked only one small cigar. He told us he had read everything that Ernest Hemingway wrote. In particular, he admired “The Old Man and the Sea,” about a Cuban fisherman, because Hemingway had written a novel “simply about a man and his thoughts.”