In “An Enemy of the People,” an 1882 play by Henrik Ibsen, Thomas Stockman, M.D., runs afoul of friends, family and other citizenry of a small southern Norwegian town when he exposes the local spa, a big moneymaker, as a hotbed of bacteria. Despites threats and bribes, he stands by his discovery, proclaiming at the end of the play that he is the strongest man in town, because he can stand alone.

But he is not alone. He stands with the truth.

Ibsen himself, who saw his play more as a dramedy than a straight drama, was ambivalent toward his hero, suggesting that he might’ve been more persuasive had he been a little less zealous. It’s understandable. No one likes the unadulterated truth, much less its messenger. We prefer to think with waggish Ibsen contemporary and literary equal Oscar Wilde that “the truth is rarely pure and never simple,” allowing us to cherry-pick those facts that are convenient. And yet, there is something fascinating, confounding and ultimately admirable about the individual who sticks to his guns with the unvarnished truth.

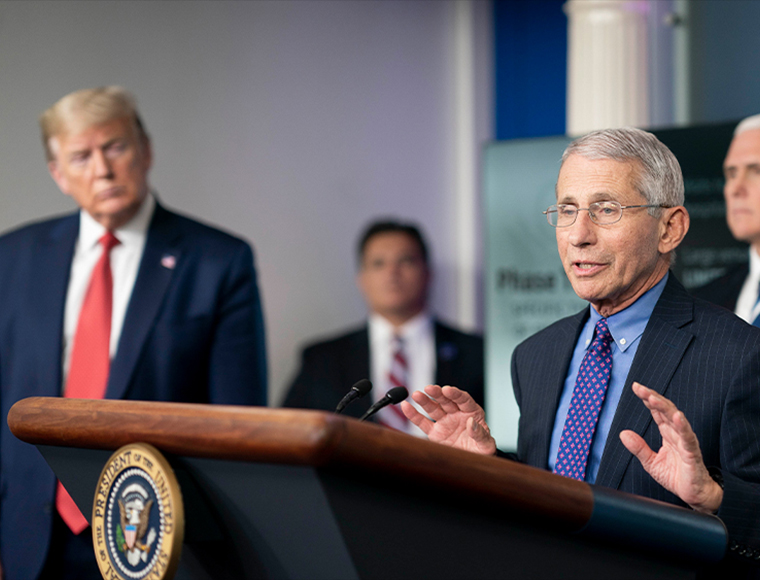

You have to wonder if Anthony Fauci, M.D. — the embattled director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, who’ll turn 80 on Christmas Eve and who began by delivering prescriptions for his parents’ Brooklyn pharmacy, sees himself in Stockman, a man we can take stock of and put stock in. Or perhaps the former pre-med classics major at the College of the Holy Cross, who received a Bachelor of Arts degree there before going on to graduate first in his class at Cornell University Medical College, would prefer to think of himself as a latter-day Cassandra, the virgin Trojan prophetess doomed by the god Apollo, whose advances she had rejected, never to be believed. That Apollo was the Greco-Roman god of plagues as much as the lord of the arts, the sun and truth makes the analogy all the more fittingly complex.

Whatever your literary poison, there’s no denying that Fauci has paid a price for his commitment to the truth about the need for an aggressive national response to the novel coronavirus and the disease it causes, Covid-19. Lionized by many on the left — Brad Pitt played him on NBC’s “Saturday Night Live” — he’s been demonized by some on the right to such an extent that he requires a security detail. His family — which includes wife Christine Grady, chief of the Department of Bioethics at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center, and three adult daughters — has been harassed. Steve Bannon, former adviser to President Donald J. Trump, has been banned from Twitter and lost his lawyer for suggesting Fauci should be decapitated. (Fauci’s long agon with the current administration and its supporters has not been without its humor. Debunking Sen. Rand Paul’s notion that New York’s relatively successful response to the virus after once being its epicenter was due to herd immunity, Fauci said, “In New York, (the herd immunity rate is) about 22%. If you believe 22% is herd immunity, I believe you’re alone in that.”

Having served six administrations — Republican and Democratic alike — without political prejudice, Fauci had seen pandemics before. Those of us who covered AIDS in the 1980s remember the good doctor well. He was then in his 40s, the prime of life, the newly minted NIAI head and once again challenged by a Republican administration that took an ostrich approach to a fearful health crisis. Then as now, there were missteps and a backlash, only then it was mainly from the left in the form of the besieged LGBTQ community, whose members felt, rightly so, that they were faceless to the government. Playwright/AIDS activist Larry Kramer called Fauci a pill-pushing idiot.

But rather than be put off, Fauci went all in, reaching out to the gay community and researching patient therapy and an HIV vaccine. With the disease now a chronic one, thanks to a complex, expensive cocktail of antiretroviral drugs, Fauci has turned his research attention to the immune system’s role in HIV infections and its response to them. Ultimately, Kramer, a part-time Connecticut resident who died of pneumonia on May 27, would call Fauci “the only true and great hero” among government officials in that crisis.

Over the years, other accolades have poured in — the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President George W. Bush in 2008 for his work on PEPFAR, the AIDS relief program; a slew of honorary degrees, including one from Johns Hopkins University in 2015; one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people this year; even special recognition at New York Medical College’s Founder’s Dinner this past October. Fauci has transcended both honors and calumny, passing into literature as Anthony Della Vida, M.D., in Kramer’s play “The Destiny of Me” and the inspiration for the physician love interest in Sally Quinn’s romance “Happy Endings.” (Those skeptical of Fauci as a romantic should know he met his wife, a nurse as well as a bioethicist, while they treating an NIH patient.)

However, the baseball-loving Fauci, who threw out the first pitch for the Washington Nationals’ home opener at the start of Major League Baseball’s Covid-shortened season, remains Theodore Roosevelt’s “Man in the Arena,” “who spends himself in a worthy cause; who at the best knows in the end the triumph of high achievement, and who at the worst, if he fails, at least fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who neither know victory nor defeat.”

He is still Cassandra on the Trojan parapets, his warnings unheeded by some; still Stockman, standing alone.

But his voice will not be silenced. Predicting a tough winter, Fauci is nonetheless encouraged enough by recent vaccine trial successes to forecast a better outlook for the second half of 2021. That all depends, though, on whether or not we take the vaccines once they’re offered and double-down on our current protocols.

“A public health message like I’m trying to give is not encroaching on anyone’s freedom,” he told Andrew Ross Sorkin, founding editor of The New York Times’ DealBook financial news service, last month. “We’ve got to do everything we possibly can to pull together as a nation and not as individual factions having differences that spill over into public health.”