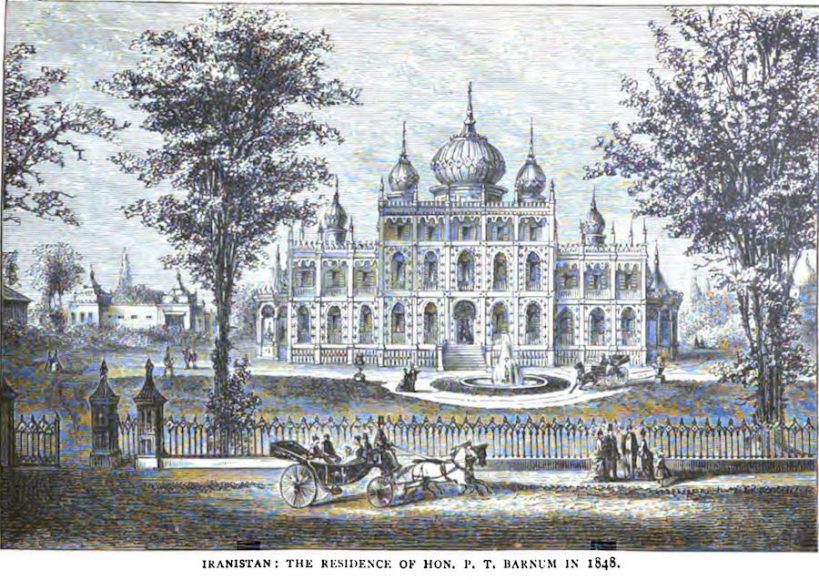

There had never been an American mansion like it before — a phantasmagorical dream worthy of an “Arabian Nights” odyssey, with grand onion domes and Moorish arches, set amid an arboreal splendor that stretched across the west side of Bridgeport. And, not unlike a dream, its brilliance was brief and its end abrupt.

The mansion was dubbed Iranistan and it served as the conspicuous residence of P.T. Barnum, the most audacious showman of the 19th century. While Barnum’s rise was fueled by increasing theatrical humbuggery, his unlikely estate presciently created the concept of the celebrity home.

The idea for Iranistan was conceived when Barnum toured England in 1844 with his diminutive star General Tom Thumb. He stopped at the seaside resort of Brighton and visited the Royal Pavilion, the residence created for King George IV, where he was enchanted by the fanciful design that mixed Indian, Moorish and Arabian styles into a fairy tale-worthy palace.

Barnum impulsively decided that he wanted his version of the Royal Pavilion in Bridgeport, where he had set up residence. “I concluded to adopt it and engaged a London architect to furnish me a set of drawings after the general plan of the pavilion, differing sufficiently to be adapted to the spot of ground selected for my homestead,” he later recalled.

Arriving home in 1845, Barnum acquired 17 acres of land in Bridgeport to accommodate his vision. The drawings he brought from London were sent to Leopold Eidlitz, a Jewish-Czech architect based in New York with no previous experience in Islamic-style design. Barnum gave the project a “spare no expense” budget and, after three years, his vision was completed by a force of 500 workmen at a then-astronomical cost of $150,000 — or $46.6 million in today’s money.

Named in tribute to what Barnum believed were its Persian motifs, the red sandstone mansion offered a three-storied central structure between a pair of two-story wings that, in turn, were flanked by glass conservatories. Intricate Moorish-style arches covered the exterior and a massive onion-shaped dome capped the house, surrounded by four smaller domes and a series of minarets. A grand fountain in the middle of a circular driveway was placed at the front of the home, which measured 124 feet across and 90 feet from the entrance to the main dome’s peak.

Surrounding the home were fruit trees, greenhouses, flower gardens and grazing pastures for livestock. A pond in the back of the property was occupied by ducks and swans. Within the home, Barnum brought the most elegant furnishings and artwork to fill an 1848 residence, with marble statues and a dining room that sat 40 guests. And in the ultimate acknowledgment to modernity, Iranistan also had bathrooms with running hot water.

While Barnum’s property stood out in mostly rural Bridgeport, the impresario went one step further by actively encouraging visitors to stroll through its grounds — albeit after planting the story that he had a pack of ferocious bulldogs patrolling the area to prevent vandalism or burglary. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle urged its readers to take the ferry to Connecticut to visit “one of the most unique and magnificent structures in the country,” and Iranistan quickly became a popular tourist destination.

Barnum hosted a homecoming party at Iranistan on Nov. 14, 1848, with 1,000 people in attendance. Author and humorist Mark Twain, publisher Horace Greeley and the English poet Matthew Arnold were among the prominent guests welcomed by Barnum. But the most important guest he attracted was the Swedish soprano Jenny Lind. Although she received numerous offers to tour the United States, Lind refused to make the extensive journey across the ocean until she received an inquiry from Barnum on stationery featuring an engraving of Iranistan. Lind confided to Barnum that she welcomed his invitation, because anyone who would build “such a palace cannot be a mere adventurer,” adding that she would have “declined if I had not seen the picture of Iranistan.” Barnum’s promotion of Lind’s U.S. tour created a cultural sensation that stretched from 1850 to 1852.

At the conclusion of the Lind tour, Barnum returned to Iranistan to host his daughter’s wedding, but a fire broke out on the roof. Mercifully, workmen had been repairing the roof that day and were able to put out the flames quickly. The wedding took place, but the building needed repairs.

Unfortunately, Barnum’s financial wealth was diluted during the mid-1850s by a series of bad investments and work on repairing Iranistan was delayed for several years. On the night of Dec. 17, 1857, another fire broke out at the residence, most likely caused by a workman who left a lighted pipe on a seat cushion within the main dome. Barnum was in New York City when he received the news the next day that the entire structure was lost to the flames.

Due to his ongoing financial woes, Barnum failed to maintain most of his insurance payments on Iranistan and only netted $28,000 from his carrier. He sold the grounds for $50,000 to Elias Howe, the sewing machine maker, which he used to pay down some of his debts.

Iranistan was never photographed and its grandeur today can only be imagined through a few lithographs and its uncommon history. America has never seen another structure quite like it, and that would fit into Barnum’s celebrated observation: “No one ever made a difference by being like everyone else.”