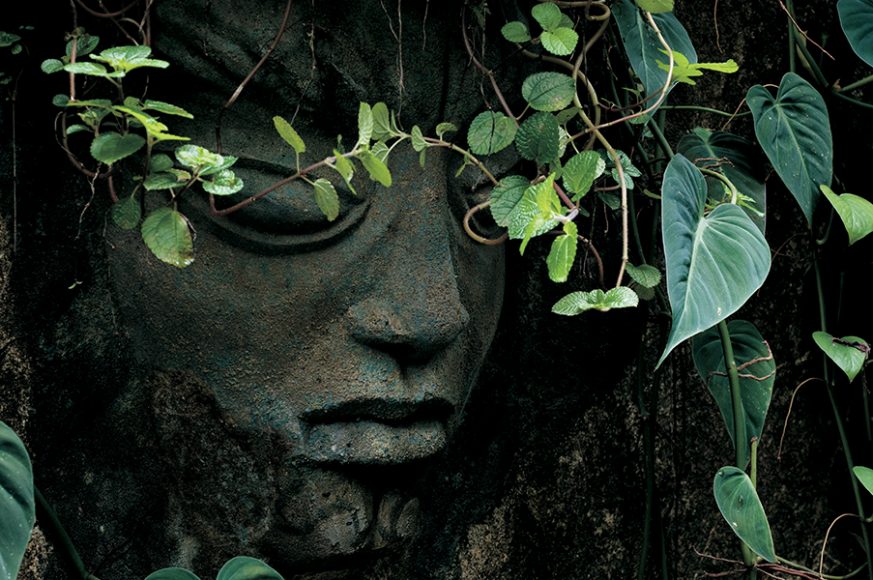

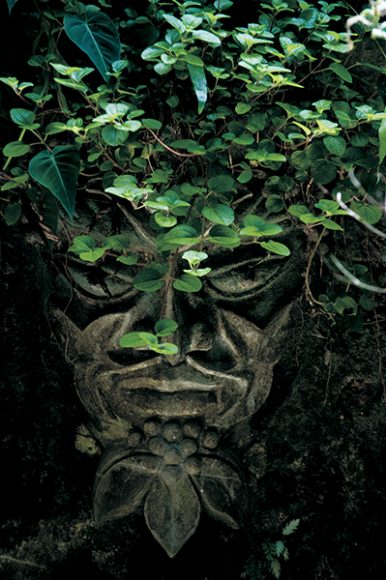

Fantastic gargoyle fountains. Planters of sculpted heads. Statues of lissome youths. Red ginger offset by lush greenery.

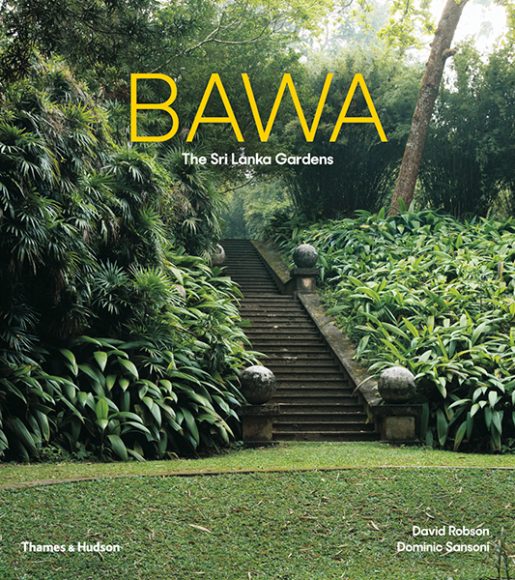

These are just some of the first impressions of “Bawa: The Sri Lanka Gardens” (Thames & Hudson, June 6, $39.95, 176 pages), which explores two complementary tropical gardens on either side of the Bentota River on the island of Sri Lanka, off the southeast coast of India.

With a text by David Robson and photographs by Dominic Sansoni, “Bawa” is really the story of two brothers, 10 years apart in birth and a world apart in sensibility.

The sons of a successful Moorish lawyer, Benjamin Bawa, and his Burgher wife, the former Bertha Schrader, Bevis and Geoffrey Bawa grew up in privilege in a verdant suburb of the capital city of Colombo during the last days of the British Empire. Bevis, the elder (1909-92), was something of a soldier of fortune, serving as equerry to five British governors while Bertha urged him toward a career as a planter. His wide-ranging interests meant that Brief, his rubber plantation in southwestern Sri Lanka, became neglected and diminished over time. But as the estate shrunk to a bungalow, the surrounding gardens became more fantastic, attracting the likes of Lawrence Olivier and his wife, Vivien Leigh, fellow actor Peter Finch and artist Donald Friend, who did the fabulous trompe l’oeil doors, colorful murals and (with Bevis) serenely sensuous urns on the property, among other objets d’art.

The more studious of the two, Geoffrey (1919-2003) was sent off to England to become a reluctant lawyer. But when he returned in 1948 and saw what his brother had done at Brief, he determined to outdo him, purchasing an abandoned estate, Lunuganga, on the far side of the Bentota River from Brief. That purchase and the transformation of Lunuganga’s landscape spurred Geoffrey to return to England to become an architect. England in turn influenced the look of Lunuganga, which is grand and formal where Brief is intimate and casual.

“He had very happy memories of his time at Cambridge and of staying with friends in the country,” Robson writes. “It was through them that he came to appreciate the subtleties of the garden planning of William Kent and his contemporaries.”

Robson continues: “But Lunuganga also speaks to that long tradition of Sri Lankan garden — and landscape-making… the bizarre boulder gardens of the first Buddhist ascetics; the rolling park landscapes of the Anuradhapura monasteries; the pleasure gardens of the Sinhalese kings; the mysterious retreats of the forest hermits; the vivid green mosaics of rice paddy; the lines of leaning rubber trees and gently swaying coconut palms; the neatly hedged lawns of the estate-bungalow gardens.”

These pleasures and more await those who visit the Bawa gardens — or read this evocative book.

For more, visit thamesandhudsonusa.com.

For more on Brief, email doolandads@sltnet.lk. And for more on Lunuganga, visit geoffreybawa.com.