Additional reporting by Georgette Gouveia.

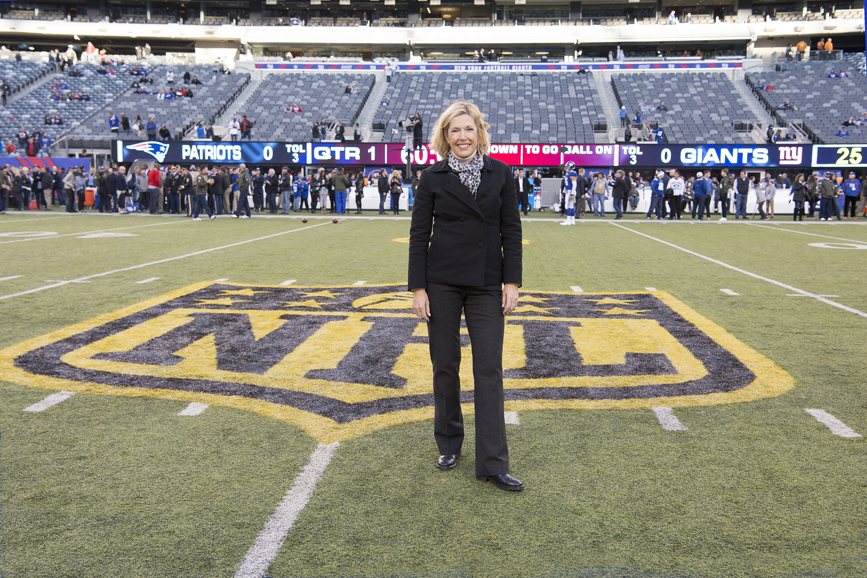

For Dawn Hudson, chief marketing officer of a “little brand called the NFL,” “football is family.”

Not only is the game — now America’s pastime — a social event with an increasingly female viewership. (About 45 percent of the audience is female.) But Hudson thinks of the NFL organization as a family — the young female assistants who may look up to executive vice presidents such as herself, the guys on the gridiron, “99 percent” of whom, she says, are big kids themselves who are happy to spend time with youngsters and promote charities, their own and those of others.

It is this message that Hudson delivered recently as keynote speaker for the United Way’s third annual Women’s Leadership Council event at Abigail Kirsch at Tappan Hill Mansion in Tarrytown. And it is this message she will continue to refine for a league that has been rocked by violence on the field (concussions leading to brain damage) and off (domestic abuse).

In these, partnerships are key, she told the 175 women — and a few good men — who gathered for the breakfast meet on a rainy morning. The NFL has partnered with General Electric to come up with technologies to mitigate head injuries.

“I do believe the NFL should make players as safe as can possibly be,” she says, noting that jockeys suffer from the most concussions.

Asked about the new movie “Concussion” — in which Will Smith plays Bennet Omalu, the forensic pathologist who fought the NFL to publicize his findings on the link between football concussions and CTE, or chronic traumatic encephalopathy —Hudson says, “It’s another opportunity to talk about the issue.”

The NFL has also teamed with No More, an organization that works to combat domestic violence, for a campaign that included a much-discussed PSA (more than 100 million views) on last year’s Super Bowl broadcast featuring several of the league’s players.

Domestic violence isn’t just a football problem, she says, but a pervasive, deeply entrenched American one for which it may take seven or eight tries before the victim leaves her — or his — abuser. That story has to get out as well, she says.

It was a September afternoon in 2014 when NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell phoned Hudson to ask if she wanted to help the NFL tell its story.

The two, both Bronxville residents, had worked closely while she was president and CEO of PepsiCo North America. (She was instrumental in the league’s transition from Coca-Cola to Pepsi as its official soft-drink sponsor.) At the time, Hudson was in the midst of selling The Parthenon Group, a Boston-based boutique consulting firm, and planned to remain with it in some capacity.

But, she tells WAG, “All I could think about was how badly I wanted the (NFL) job.”

“Little did I realize how much (Goodell) needed me,” she says.

Having decided it was an offer she couldn’t refuse, Hudson nonetheless went off with her mother on an 80th birthday trip to Africa — where cell phone service was patchy. She returned to discover the NFL had been blitzed. A video of Baltimore Ravens’ running back and former New Rochelle High School star Ray Rice cold-cocking his then-fiancée (now wife) Janay Palmer in an Atlantic City elevator had been leaked, and the league — a $45 billion business — was under attack.

“We are no different than society,” Hudson tells WAG. “Our players and employees are magnified under a microscope. It’s all about the speed with which you react. There is an importance to transparency.”

To retain that transparency, Hudson’s team works with the 32 franchises and their owners, media partners and corporate sponsors to craft an entertainment that appeals to both the casual and the hardcore fan.

She oversees the Scouting Combine, the annual draft, the Super Bowl and the league’s international games, played in London in October and November. This year, she helped spearhead the Super Bowl High School Honor Roll, a $1 million campaign that allows schools to apply for grants of up to $5,000 to expand and improve their football programs. The Honor Roll also awards a commemorative golden football to each high school that has produced a player or coach who has participated in the program. It’s a feature of Super Bowl 50, which is set for Feb. 7 at Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara, Calif.

The Honor Roll is just one of the NFL’s youth initiatives. Its Play 60 program — designed to put kids on a physically fit, nutritionally sound footing — is a partnership with the United Way.

“Big brands can always have an impact, but sports are also a way in which you can touch people,” Hudson says. “That’s the fun of this job — creating something with many people and making a difference.”

Hudson has always enjoyed sports and being creative. At a “small college in New Hampshire” called Dartmouth, she played tennis and golf. (She would later become chairman of the board of the Ladies Professional Golf Association.)

But she also loves advertising and would go on to work for such agencies as DMB&B and Omnicom. It was while she was at Dartmouth that she interviewed for an advertising job. When the recruiter followed up, Hudson’s mother suggested he was sweet on her. Hudson was shocked.

“Mother,” she recalled saying. “This is about a job.”

But two years later, dear reader, Hudson married Bruce Beach.

“That’s why I tell my daughters (Morgan and Kendall), ‘Always listen to your mother.’”

On any given game day, mom can be found on the sidelines or in front of the tube.

“Something new happens every Thursday, Sunday and Monday,” she says. “It’s all about staying on top of the job.”

Hudson will be at the Super Bowl, but like the league’s other 599 employees, she won’t have a rooting interest. Or rather, week in and week out, from moment to moment, they all root for the underdog.

“We just want to see a good, close game,” she says, “that keeps everyone involved.”