A horse is more than a pet to its owner; it is a partner.

It has been said that when a person rides a horse, the two become one.

The bond grows closer over the years – even decades – as a horse can live into its 30s and 40s.

In the mid-Hudson Valley, horse lovers can select from a wide variety of facilities for boarding, breeding and riding as well as helping people and horses to heal.

Hal and Beverly Eisenberg of the 21-acre Run Free Farm in Brewster offer clients 100-plus acres of trails thanks to an agreement with a neighbor.

The Eisenbergs are beneficiaries of another neighbor’s endeavors. “The City of New York, to protect its watershed, paid to build us a composting pad,” Hal says. “Periodically the compost is transported to farmers to use on soils.”

The Eisenbergs take pride in knowing that the horses they board bed down on straw, not wood shavings. “The straw composts more easily. It is mucked out every day,” Hal adds.

Also in Brewster you’ll find Pleasant View Farm, 90 acres of open land and trails managed by Ervin Raboy. He contrasts the horse industry in eastern United States with that in the Midwest and West: “Here it’s mostly English riding for pleasure or entertainment. There are still working horses out west.”

Raboy is impressed with the pluck shown by riders who have fallen on his and other farms. A retired emergency medical technician, he can provide first aid to fallen riders.

“Even with permanent disabilities, they want to get back on that horse,” he says.

“I see fewer children riding now,” he laments.” “Many are tied up with school team sports and activities and find no time to care for a horse. If there aren’t children growing up riding, in the future there won’t be adult riders,” he says with a grimace.

Raboy devotes a day a month to the future of agriculture, volunteering on boards and lobbying legislators.

Erica Albrecht of Pond View Farm in LaGrangeville owes her career to her mother’s catering at the Poughquag, N.Y., home of Franklin Delano Roosevelt Jr. Ten-year-old Erica had tagged along with Betty Albrecht to help and caught FDR Jr.’s attention.

“He was seeking a young rider to exercise and show his four ponies,” she recalls.

Horsemanship was no stranger to Albrecht. Her father, Richard, is a farrier, shoeing horses.

When FDR Jr. gave her a pony, she commuted the several miles from her home to his on her pony. “I could not do that today. The open space is gone,” she says wistfully.

The 42-acre Pond View Farm is owned by her parents and operated by Albrecht.

“We are fortunate,” Albrecht says. “Many horse farms are landlocked by development, but 500 acres of an adjacent retired dairy farm was donated to Union Vale, becoming Tymor Park. Our clients ride trails there.”

The 25 to 30 child clients ride in a noncompetitive environment.

“It’s an oasis in which kids can just be kids,” Erica says. The farm is open Saturdays and Sundays so that children do not have to be torn from after-school activities.

Leslie Heanue is founder and executive director of the Therapeutic Equestrian Center in Cold Spring, which serves mentally and physically challenged individuals.

Heanue owns and trains the horses, selected to fulfill their specialized mission. The center, with 65 clients, serves children and adults with autism, Down syndrome, head trauma, cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis and other disabling conditions.

“The horses are matched with the riders,” Heanue says. “We have horses with bigger barrels (rib cages) for clients with balance issues and horses with narrow shoulders for those with less mobility in the hips and spread of legs.”

Two instructors are certified by the Professional Association of Therapeutic Horsemanship International.

The farm boasts 35 core volunteers who receive training to serve as leads and side walkers. “Each client starts off with one lead and two side walkers,” Heanue explains. “As clients progress, they ride independently.” Other volunteers clean stalls and paddocks, groom horses, repair fences and work in the office.

Putnam County Legislator Barbara Scuccimarra, a former horse farm manager, is among the volunteers. Observing the physically challenged, she notes, “Every week I see improvement in these individuals when they get off the horses.”

The farm has embarked on a project to help disabled veterans, working in cooperation with the Team Red, White and Blue chapter at West Point and Hearts for Heroes in Bedford.

Individuals with special needs also find a variety of therapeutic horses to partner with at Pegasus Therapeutic Riding in Brewster and its chapter affiliates – Fox Hill Farms in Pleasantville, Kelsey Farm in Greenwich and Ox Ridge Hunt Club in Darien.

At Fox Hill, a child might have a love affair with Cinnamon, a large Appaloosa pony; at Kelsey, maybe Frankly and Elmo, a pair of look-a-like Welsh cross geldings; at Ox Ridge, perhaps Classico, a Canadian-born Tobiano/Warmblood gelding, and at Pegasus Farm, maybe Pi, a former racing Thoroughbred.

Participants at the four farms include individuals with special needs, military veterans and at-risk individuals, including disadvantaged youth and abuse survivors.

Directing operations at the Brewster headquarters is Todd Gibbs, who was in management with nonprofits when therapeutic horseback-riding was recommended for his two daughters with special needs. Approached by Pegasus, Gibbs now serves as executive director.

Parents and volunteers cheer riders on. One mother says, “Seeing our son always just a spectator was difficult.” Now he’s the one in the ring, she says, adding with pride, “When he gives a high five, we know he feels like the most valuable player of the World Series.”

One volunteer with a 22-year history at Pegasus observes, “When a child with cerebral palsy takes his first step on the ground because of the motion he learned from his horse or when a blind rider finds the confidence to let his horse help him move safely in space – these are miracles.”

Hot To Trot Stables is a neighborhood horse farm in Cold Spring. Laurie Yodice, its owner, counts 30 to 40 riders who traverse its seven-plus acres on their mounts.

Yodice and her daughter Rachel run the operation, including care of five horses and ponies. Zoning regulations prohibit more, but careful scheduling gives all an opportunity to ride.

“Children arrive from school and are hands-on, learning to groom, and then begin the lesson,” she says.

Not all Hot To Trot riders are young. “We had this 50-year-old woman who never rode a horse,” Yodice says. “She ran into the woods when one came down the road. She didn’t want to be afraid any more. She broke in slowly with just grooming and touching, had a couple of lessons and got over her fear.”

The stable’s owner formerly worked in the retail field. Upon marrying, she looked to move to a country setting and 18 years ago settled on the plot where the stables are now situated.

“I bought my first horse at age 42,” Yodice recalls. “Horses are herd animals. This horse needed a companion. I went to a rescue farm and was drawn to a horse that had been locked in a stall on an abandoned farm, left for weeks without food or water. He was up to his knees in his own manure, which is all he had to eat. He had bruised and cut his body banging it against the stall trying to escape. He was 600 pounds and should have been 1,000. He had such a look in his eyes. I went home and cried. I couldn’t get him off my mind.”

The rescue farm ultimately called, reporting that the horse had responded to care and could be adopted. “He was still not fully recovered. We had a long road to go,” she recalls. “Sundance, as I named him, became hardy enough to compete and was in a show with very expensive well-trained horses. When he won the grand championship, I asked the announcer to mention that he was a rescue horse and for people to consider adoption.”

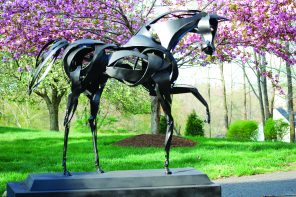

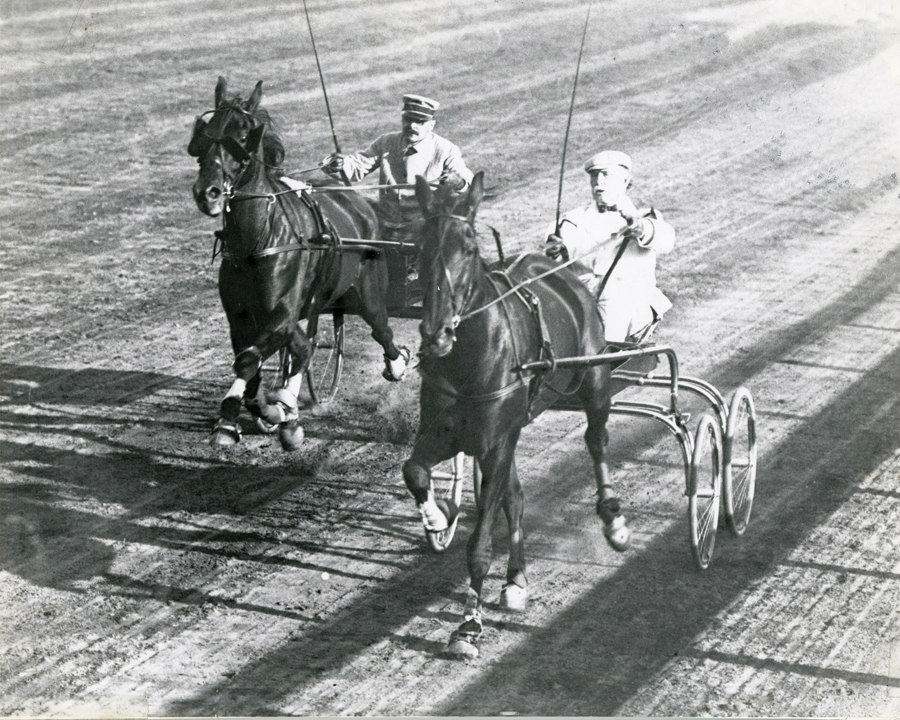

Horse fanciers have a continuing source of horses to ride and race thanks to breeding operations like Wallkill’s Blue Chip Farms.

The farm is owned by Thomas Grossman. Assisted by Michael Kimelman, president, and Jean Brown, vice president of operations, the farm breeds both Standardbred racehorses and Warmbloods.

The mares are artificially inseminated. The stallion takes his inspiration from a mare in heat, with sperm collected and prepared with an extender, the goal being to impregnate three or more mares from one collection. “At present we have nine commercially active stallions,” Brown reports. “The oldest stallion here is age 30 and no longer services mares.

“A veterinarian determines through ultrasound when mares are coming into heat and should be inseminated. Gestation time is 11 months.

“We foal out about 150 mares a year. About 50 return to their owners’ farms. We raise about 100 foals per year here until they are ready for auction.”