It’s hard to keep up in conversation with Nathan Lewis. The slouchy sensibility of a skateboarder with black cap, black turtleneck-T and blue denim pants with red stitching belies what’s ticking in his skull.

(Think Nietzsche, Trump, privileged white male, cellphone culture, literature, #MeToo movement, science, philosophy and, oh yes, narrative painting. And then he’s riffing on Ovid’s “Apollo and Daphne.”)

The painter and associate professor of art at Sacred Heart University corrects the assumption of a visitor to his Seymour studio and says while he might have done some skateboarding in his younger years, his passion was BMX riding. He had a half-pipe in his parents’ backyard in Sacramento where he and his friends would perform acrobatic stunts on those sturdy, tiny-framed sport bikes in the California sun. By his own admission he was a daredevil, but he wasn’t pro material like his pals.

It was the end of the ’80s and a young Spike Jonze was documenting the skateboard and BMX culture on video, while buddy Andy Jenkins was doing the same in print with Mark “Lew” Lewman at Home Boy and then Dirt magazine.

Lewis liked what he saw. He cut his teeth as a publisher of his own zine that covered his fellow BMXers’ exploits. He was photographer, writer, layout artist and printer via a Xerox machine.

For the next few years he was in and out of college navigating through different disciplines — engineering, photography and art. 1993 found him in St. Petersburg, Russia. He lived just a few blocks from the State Hermitage Museum housed inside the immense Winter Palace next to the Neva River. He was a constant visitor, breathing in its collection of Leonardos, Rembrandts, Rubens and Riberas, and then waiting to exhale.

One day the curtains in a section of the museum that was usually closed happened to be open and the daylight played across Rembrandt’s “Sacrifice of Isaac.” Abraham was ordered by God to kill his son. In the painting, an angel grasps Abraham’s hand. The long, curved knife it held is

suspended in air. Abraham’s other hand covers his son Isaac’s face. The light. The shadow. The detail of the faces. It catches your breath. It caught his breath.

“I was in a state of arrest for a half-hour,” Lewis says.

The size of the painting — 52 by 75 inches — was probably another subtle influence on Lewis, as were the other Rembrandts.

In Lewis’ owns works as well, it’s go big or go home.

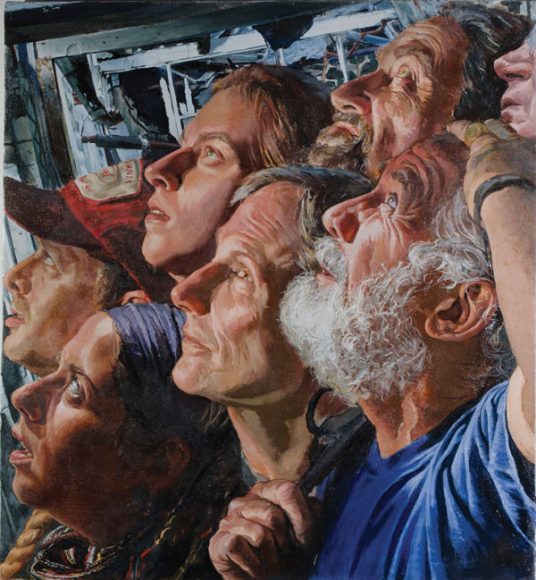

“Till We Find the Blessed Isles Where Our Friends Are Dwelling” (2008, 72 by 120 inches) is Lewis’ acrylic reinvention of artist Emanuel Leutze’s 1851 depiction of “Washington Crossing the Delaware.”

The painting’s title is a phrase from Friedrich Nietzsche’s “Thus Spake Zarathustra,” a book in part about eternal recurrence. The blessed isles are a heavenly paradise. It was near the end of the second term of President George W. Bush (a Texas oilman who in July 2008 had lifted an executive order banning offshore oil drilling) that Lewis wondered how a new America would be represented. Choosing Leutze’s painting, Lewis tells a narrative of young adults trying to achieve their respective futures, just as Washington and his men were seeking American independence through a secret attack on Hessian and British forces in Trenton, New Jersey.

Washington is replaced by an Asian-American woman who is holding a tiny oil derrick. She is also seen near the back of the boat holding a doll while the oarsmen — including one who looks like Lewis — battle rapids and navigate past a large rock. The American flag is torn. The passengers are multicultural. A gas can attached by a rope trails behind the boat. Perhaps a reference to a fight to gain energy independence from foreign oil.

Lewis says he is interested in how art can tell multiple stories.

“Art is a way to create dialogue. With this administration, there are so many movements, people are speaking up more… black lives matter… #MeToo… more social consciousness… It’s an interesting time to be an artist due to the political climate.”

Lewis mentions the Vietnam War protests: “I look back on those times and we’re going through that now. We don’t trust our leaders.”

On the day of the visit to his studio, another movement — feminism — was evident on a large scale.

Lewis’ latest work in progress was hanging on a wall. It’s a stark departure from his color-filled paintings. This one is about 7 feet tall and consists of a charcoal drawn female figure holding a banner. The finished artwork will be Lewis’ submission for the Nasty Women Connecticut’s third annual Art Exhibition to be held March 8 in New Haven. The title of the exhibit is “Complicit: Erasure of the Body.”

Nasty Women Connecticut began as part of the international art movement in the first days of Donald Trump’s presidency. Its mission statement in part reads, “We use art as a vehicle of communication to unite all communities in our local area and we demonstrate solidarity in the face of threats imposed upon so many of our own neighbors by the current administration.”

That goes hand in glove with Lewis’ philosophy about using art as a dialogue.

“For me, part of the process is trying to understand some of the difficulties women have to go through. As a privileged white male, have I been complicit?”

Working on a roll of heavyweight drawing paper, Lewis first covers it with charcoal and then using different size erasers creates the female image.

His inspiration? “I had a dream of a figure holding a flag in a wasteland. Paintings come from dreams sometimes.”

For a look at more of Nathan Lewis’ works, visit alvarezgallery.com/artist/Nathan-lewis.