Fashion designer John Galliano begs one of the most challenging questions for lovers of the arts today: Can you separate the artistry from an artist who has scandalized through racist or sexist behavior?

In 2011, just before the debut of his autumn-winter collection at Paris Fashion Week, Galliano was arrested in a bar for an anti-Semitic outburst. (In France, it is illegal to make anti-Semitic remarks.) He was subsequently dropped from Dior, where he had been head designer since 1996.

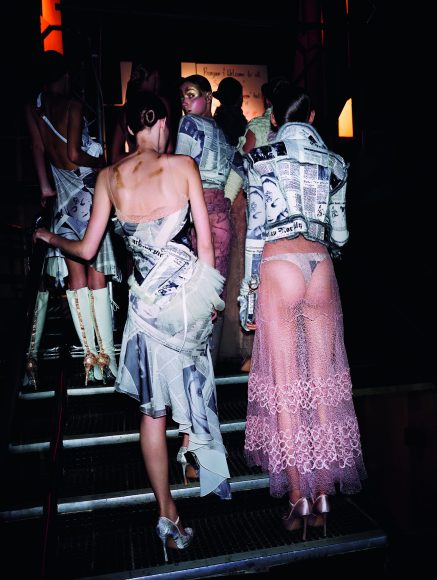

That incident, resulting trial — in which he was found guilty and received a suspended fine of 6,000 euros, or roughly $6,578 in today’s money — as well as subsequent civil lawsuits are nowhere to be found in “John Galliano for Dior” (Thames & Hudson, Nov. 5, 431 pages, $150). With more than 400 color illustrations by photographer Robert Fairer; a foreword by Hamish Bowles, a preface by André Leon Talley, an introduction by Oriole Cullen, an essay by Ivan Shaw, collection texts by Iain R Webb and creative direction by Daniel Baer, the sumptuous tome is for the hardcore fashionista and Galliano fan. Those looking for insight, however, into the character of a man whose edginess has been both his blessing and his curse will have to look elsewhere. It’s like reading a book on the Titanic that omits the iceberg.

For that matter, those looking for insight into his creativity might have to look elsewhere as well. There are lots of stylish words here by experts, but what raises Galliano’s creations to the plane of art eludes them. They fail to encapsulate a style that built on the romantic, feminine aesthetic conjured by Christian Dior in the postwar era — the so-called “New Look” — by plumbing the outrageous, decadent and erotic in richly textured, luxuriously patterned and brilliantly colored clothes that reflected a profound love and knowledge of the arts. Think of the sleeveless chartreuse satin Chinoiserie gown — with its deep slits up the sides and floral embroidered embellishments — that Galliano designed for Nicole Kidman for the 1997 Oscars. Galliano had just shown his first collection for Dior, and people still didn’t know what to make of him — or the dress and its fluorescent tennis-ball green hue.

Galliano has always found inspiration in the Far East, as his 2006-07 spring-summer “Madame Butterfly” collection, featured in the book, attests. It included a strapless white, floral print gown with a fitted bodice and bell-shaped skirt wrapped kimono-style in yards of red and green-print fabric that married the Giacomo Puccini opera to the Belle Époque’s late 19th/early 20th century hourglass silhouette. It was a gown worn memorably by Dior spokesmodel-actress Eva Green (“Casino Royale,” “Penny Dreadful”), a French Jew who defended Galliano after his anti-Semitic rant, saying she didn’t think he was racist, just probably drunk. (At his trial, his lawyer cited work-related stress and multiple addictions.)

But then, Galliano has always seemed to be his own worst enemy. He was born Juan Carlos Antonio Galliano-Guillén on the British isle of Gibraltar to a plumber, Juan Galliano, and his wife, Anita, a Spanish flamenco teacher who always dressed their only son to the nines. When Galliano was 6, his father moved the family to England in search of work. It couldn’t have been easy for a shy little boy — the child of a strict Roman Catholic family — in 1960s England, and indeed Galliano was bullied in grammar school for his artistic leanings.

Those would pay off at Central Saint Martins, an art college from which he graduated in 1984 with a first-class honors degree in fashion design. The school has produced a Who’s Who of art and fashion luminaries, including Bowles, Vogue European editor-at-large, who in the book’s foreword remembers Galliano as a young man burning the candle at both ends — working as a dresser at the National Theatre and partying at night, attending class and studying by day. His graduation collection — which channeled the dandified Incroyables of post-Revolutionary France as a response to the starch of Thatcherism — was such a sensation that it was gobbled up by Browns, which Bowles describes as “London’s most influential fashion store at the time,” and by customers like Barbra Streisand and Diana Ross.

And that should’ve been the beginning of an unbroken trajectory to the top of the Paris fashion world. But qualities are defined by context, which drives perception, not by any inherent goodness or badness. The otherworldliness that fuels an artist is often of little help to the businessman. Galliano’s lack of business savvy and love of the nightlife ultimately found him bankrupt in London. However, a change of fortunes awaited him on the other side of the English Channel.

In Paris, he eventually made his way back, thanks to the patronage of Portuguese socialite São Schlumberger and New York venture capitalist John Bult, engineered by Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour and André Leon Talley, the White Plains resident who was then Vanity Fair’s European correspondent before becoming Vogue’s American editor-at-large. “That autumn/winter presentation (in March 1994) is now considered by leading experts and fashion historians to have been the show that redefined modern fashion,” Talley writes in the book’s preface.

It was Wintour who would come to the rescue again when after a golden period at LVMH-owned houses Givenchy and Dior, Galliano was tarnished by his racist rant. She brokered an invite from Oscar de la Renta for Galliano to help prepare de la Renta’s fall 2013 ready-to-wear collection for New York Fashion Week. Offstage, a now-chastened Galliano’s efforts at atonement earned the praise of the Anti-Defamation League, and many observers thought he might succeed de la Renta, a Kent, Connecticut, resident who died in 2014.

Instead just weeks before de la Renta’s passing, he joined Maison Martin Margiela (again apparently with Wintour’s blessing as she subsequently wore a Martin Margiela gown to the British Fashion Awards).

Since then the vegetarian has renounced the use of fur in his collections and has designed Martin Margiela’s first fragrance, Mutiny, a tuberose leather whose femininity is said to transcend gender.

“There are no normal ways to talk about Galliano,” Talley writes in the book’s preface. “His work provokes an emotional experience that exalts the senses. Yes, I can imagine you could imagine tasting the looks…. Every sensory perception is built up to sustained moments of sheer wonder….He is able to align such diverse elements of inspiration, coupled with high technique, that it borders on ‘art’ in high fashion.”

For more, visit thamesandhudsonusa.com.