Gardens and photography complement each other.

The photograph is framed by the past, frozen in time. Not so the garden.

“I’m always conscious of the garden changing every year,” landscape photographer Larry Lederman says, adding that the seasons are never the same. And trees, like old friends, pass away. “Heartbreaking,” he says.

Loss occurs even in well-tended gardens, he notes. “And if you don’t take care of them, you discover fast how run-down they become.”

The photographer, then, tries to capture what will soon be a memory.

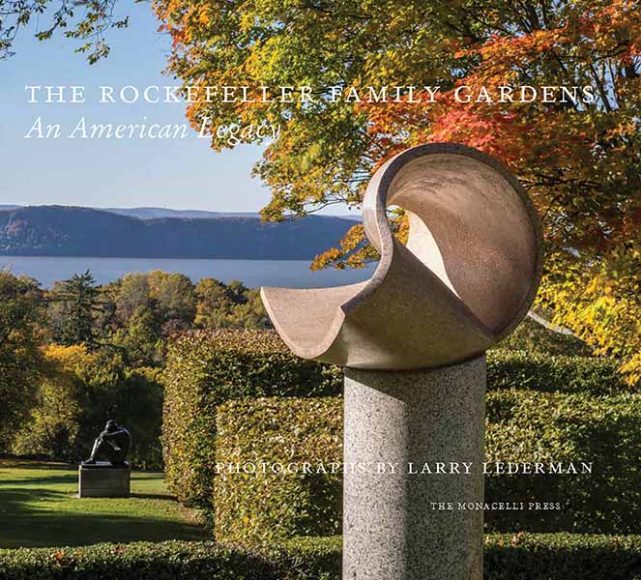

The frisson created by the tension between photography’s permanence and the garden’s evanescence plays out exquisitely in Lederman’s latest book. “The Rockefeller Family Gardens: An American Legacy” (Monacelli Press, $50, 199 pages) presents readers with the evolving landscape of Kykuit — the Rockefeller estate overlooking the Hudson River in Pocantico Hills, now a national landmark — as seen through the three titans who shaped it. John D. Rockefeller Sr. built Kykuit. His son, John D. Jr., oversaw the design and completion of the house and its neoclassical Beaux Arts gardens by William Welles Bosworth. And his son Nelson, the onetime American vice president and New York state governor, used Kykuit’s garden “rooms” to site his Modern sculpture collection superbly while also resurrecting the little-known Japanese Garden. (Indeed, “The Rockefeller Family Gardens” is the first extensive exploration of the Japanese Garden in book form.)

The gardens of Kykuit (which means “lookout” in Dutch) are the yang to the yin of the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Garden at The Eyrie, the family’s summer home in Seal Harbor, Maine. The Maine garden was created by landscape architect Beatrix Farrand, niece of novelist and garden author Edith Wharton, for Abby, wife of John D. Jr. and a founder of The Museum of Modern Art. And it is at the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Garden that our story really begins, because it was where Lederman began.

“I saw a black-and-white set of photographs of a garden in Maine and it looked very spectacular, very interesting,” he says. So he determined to visit this private garden, which is open only one day a week at summer’s height to a limited number of visitors. There in a forest he discovered what he calls “a work of the imagination, because there are no centerpieces of annuals and perennials, no flower beds in Asian gardens.” And yet, Farrand, who had never been to the Far East, had created in a Maine woodlands her idea of a Chinese walled garden.

“The walls are set at high angles,” Lederman says. “You realize the amount of earth-moving equipment that must’ve been used and that Farrand was really a landscape designer.”

One of Lederman’s gifts as a photographer is to capture the way gardens conceal and reveal at the same time. The reader follows along the pink walls, crowned with richly carved, flame-colored tiles and a pagoda to peer through the Moon Gate at the Buddha Shakyamuni and other delights. But nowhere is the theme of concealing and revealing better illustrated than at Kykuit, not far from Lederman’s Chappaqua home.

There Hercules takes a whack at the Nemean Lion amid hedges and pines. George Grey Barnard’s “Rising Woman” seems to find her footing tentatively on the lawn below the forecourt, hugging her nude body. And Alexander Liberman’s “Above II” delivers a shock of red metal veiled by the copper beech grove John D. Sr. planted in 1909.

Most sensuously, Aristide Maillol’s “Bather Putting Up Her Hair” is protected by topiaries in the Inner Garden on which her pert butt rests. It’s as if we are all Davids come upon a latter-day Bathsheba.

The intimacy and openness of Kykuit reaches its zenith in the Japanese Garden.

“I fell in love with this place,” Lederman says. “It’s like walking into another world.”

He crystallizes that world in images by turns startling and serene — a cascade of fiery, serpentine Japanese maples, sighing cherry blossoms, whistling bamboo, placid stepping stones set in gravel and a teahouse reflected in a pond. He calls this section of the book “my homage to Nelson.”

Lederman’s achievements are all the more impressive when you consider that photography is his avocation, not his day job. He is a retired partner with Milbank, Tweed, Hadley & McCloy LLP, an international law firm whose clients have included the Rockefeller family. (The firm handled the legal aspect of Rockefeller Center’s construction.) Lederman is still of counsel in Milbank’s New York office, is chairman of the firm’s international corporate practice and teaches at New York Law School.

He sees a connection between the law and photography.

“The law is conceptual,” he says of the specialty that has made him one of the most influential lawyers in his field, mergers and acquisitions. “And photography is conceptual. The artist decides what he wants to record. You walk around seeing different perspectives.”

When he started taking photographs 15 years ago, those perspectives eluded him. He would take pictures of trees — a passion — on his 12-acre, lakeside property in Chappaqua that includes woodlands, roses and a vegetable garden. (He credits wife Kitty Hawks, the interior designer and daughter of the late socialite Slim Keith and film director Howard Hawks, for the landscape’s aesthetics.)

Soon, Lederman was taking photos of trees at the New York Botanical Garden, where he has been a director since 1996. His first efforts were, he says, “awful. But no matter what, I thought, at least I have a record.”

That record became much better, resulting in his book “Magnificent Trees of the New York Botanical Garden.” He’s also a contributor to “Interior Landmarks: Treasures of New York” and “The New York Botanical Garden.”

Now he’s aiming his digital Nikon and Pentax Medium Format cameras at Olana, the historic Hudson, New York, home of Hudson River School painter Frederic Church, and Peckerwood Garden in Hempstead, Texas.

These no doubt will yield more adventures in the permanence of the impermanent.

For more, visit monacellipress.com.