When we think of gardens, we tend to think of public and personal places of enchantment — England’s Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew or, closer to home, the New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx.

Or perhaps your grandmother’s garden, where you played as a child, amid “a tangle of summer birds flying in sunlight, a forest of lilies, an orchard of apricot trees,” as described in Judy Collins’ song “Secret Gardens.”

But gardens are ever-changing. The “secret gardens of the heart” that Collins recalls become “a patch of brown lawn and a fence that hangs standing and sighing in the Seattle rain.” They mirror nature’s caprice and our own. So it is no wonder that these oases of enchantment can also be places of crucible and cruelty, mystery and madness, decay and death.

The Hebrew Bible offers some of the earliest and most prominent explorations of the garden’s contradictory nature and our own ambivalence to it. As a desert, nomadic people, the ancient Hebrews gave gardens, with their vegetation and water, pride of place. The garden was not only useful in sustaining life with its plant offerings; it was a wellspring of floral pleasure that nourished the soul (the Books of Genesis, Numbers and Jeremiah). The garden was a seat of both community and meditative solitude (the Book of Esther) and the fitting resting place for the rulers of Judea (the Second Book of Kings).

The garden then was not merely the respite of the righteous; its elements were analogous to the righteous themselves. Thus Psalm 1 describes the just man as “a tree planted near running water that yields its fruit in due season and whose leaves never fade.”

But the garden could also be the place of idolatry, in which the Jews forgot their covenant with God (the Book of Isaiah). Never is that disobedience more apparent than in the story of Adam and Eve, in which the first couple forsakes the Eden where God walks in “the cool of the day” for godlike knowledge and Luciferian rivalry and defiance. Gardens are not without their perimeters, offering as they do nature framed and contained. By refusing to live within those perimeters, Adam and Eve find themselves cast beyond them into a land east of Eden and a life of labor and suffering. They lose what they do not understand.

The Christian Bible offers a reverse mirror of the Hebrew one, presenting Jesus as the new Adam who brings the covenant with God full circle. But first he has to endure his own garden crucible, in Gethsemane on the Mount of Olives near the Old City of Jerusalem. After much anguish in which he prays to be spared his coming Passion, Jesus surrenders to God’s will. He submits to the limits God had set so he can transcend them on the cross.

Still, life remains a thorny venture. “’Tis an unweeded garden that grows to seed,” a heartsick Hamlet says of the world. “Things rank and gross in nature possess it merely.”

Throughout “Hamlet,” Shakespeare contrasts appearances and reality, what seems and what is in the rank garden that is Denmark. There Hamlet feigns madness to trap his Uncle Claudius — who murdered Hamlet’s kingly father, after all, in a garden, stealing his crown and wife in the process. But Hamlet tells his frenemies Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, “I am mad north-north-west. When the wind is southerly, I know a hawk from a handsaw.”

It is Hamlet’s sometime love, Ophelia, who — caught in his game of wits with Claudius — really goes mad. And that madness plays itself out in her heartbreaking relationship with the natural world.

“There’s rosemary, that’s for remembrance,” she says. “Pray, love, remember. And there is pansies. That’s for thoughts. There’s fennel for you and columbines. There’s rue for you, and here’s some for me…. There’s a daisy. I would give you some violets, but they withered all when my father died.”

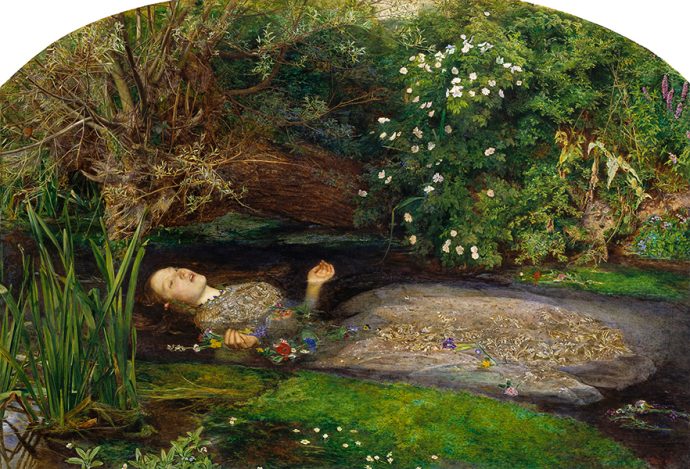

A short time after the mad scene, Gertrude — Hamlet’s mother and Claudius’ wife — returns to the stage to tell Laertes, Ophelia’s vengeful brother, how his sister died. Attempting to hang fantastic garlands of crowflowers, nettles, daisies and long purples on a willow, she fell in a brook when a bough broke and drowned, weighed down by the water, wreaths and her own oblivion.

The Bard had to describe what theater directors and filmmakers can now depict. Indeed, John Everett Millais’ oil painting “Ophelia” (1851) — one of several Pre-Raphaelite works on the theme — was the inspiration for Ophelia’s death scene in Kenneth Branagh’s 1996 film of “Hamlet.” Hollywood has long had a fatal attraction for gardens. Who can forget the ladies’ garden club that becomes a metaphor for the Communists’ nightmarish brainwashing of American soldiers in “The Manchurian Candidate” (1962)?

The garden takes on a sinister cast in “Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil.” The 1997 movie is based on John Berendt’s novelistic nonfiction work about a New York magazine writer caught up in a cagey Savannah antiques dealer’s murder of a hot-blooded male prostitute (described as “a good time not yet had by all”).

Dripping with Spanish moss, Southern Gothic characters and a tone reminiscent of Truman Capote’s and Norman Mailer’s nonfiction novels, the book and the movie poster have made effective use of Jack Leigh’s photograph of the eerie “Bird Girl” statue that once stood in Savannah’s Bonaventure Cemetery. (It’s now in the city’s Jepson Center for the Arts.)

The garden of the title, however, refers to the cemetery in Beaufort, South Carolina, where the voodoo priestess character performs incantations to ensure the antiques dealer’s acquittal at trial.

That, however, is hardly the end of a story that plumbs the garden’s — and man’s — shady side.

But for all its shadow, the garden can also reflect the soul’s reawakening. In “The Secret Garden,” the oft-adapted children’s novel by Frances Hodgson Burnett, a loveless orphan comes to live at her uncle’s English manor where a mysterious, neglected walled rose garden holds the estate’s unhappy inhabitants in thrall.

By unlocking the garden’s mysteries and reclaiming its beauty, the characters in turn come to care for themselves and one another.