“The eyes are the mirrors of the soul.”

That statement may have become a cliché, but it contains a great deal of truth. In life and in art, the expression in someone’s eyes says a great deal without words. Nowhere is it more intriguingly displayed than in the tiny pieces of painted jewelry known as eye miniatures. Or, more romantically, lover’s eyes.

These charming tokens were an upper-class fad from the 1790s to the 1830s. It was an era when public displays of affection were frowned upon and contact with members of the opposite sex was governed by strict social conventions.

So, long before selfies and sexting, people found a discreet way to convey their feelings by means of an artful depiction, on a small piece of ivory, of their amorous gaze. These intimate tokens probably first appeared in France not long before the revolution, but they became a craze in England because of a royal romance.

The young Prince Regent, later to become King George IV, had fallen in love with a beautiful widow named Maria Fitzherbert. He had a miniature of his own eye painted and sent it to her with a proposal of marriage. She reciprocated with a portrait of one of her own eyes.

The romantic gesture worked, after a fashion; Maria rather reluctantly went through an illegal marriage ceremony — illegal because she was a twice-widowed Roman Catholic, and members of the royal family, whose sovereign also headed the Church of England, could not marry Catholics. She was soon set aside and the prince married an approved cousin. The marriage was a disaster and George remained devoted to Mrs. Fitzherbert for the rest of his life.

The fashion for eye miniatures soon spread among the fashionable. For the next 50 years, the delicate pieces (they were given the name of lover’s eyes recently by New York antique dealer Edith Weber) were treasured love tokens.

The little paintings were especially intimate since usually only the wearer and the subject knew the “eye-dentity” of the beloved. Usually the miniatures were set in gold and artfully surrounded with gems such as pearls. They were worn especially as lockets by both men and women, where they could nestle against the bare skin. Less romantically they were also mounted as brooches, lapel pins and rings and on male accessories such as snuff box lids, toothpick holders and cane handles.

Not all lovers’ eyes were tokens of romantic love. Some, called tear jewelry, were memorial examples. Others were sentimental symbols of affection. Queen Victoria popularized a minor revival of eye miniatures as presentation pieces for family members and favored friends.

One of the most intriguing and unusual examples of this genre is not a depiction of an eye at all. Even more remarkably, we know not only exactly for whom it was painted, but who painted it.

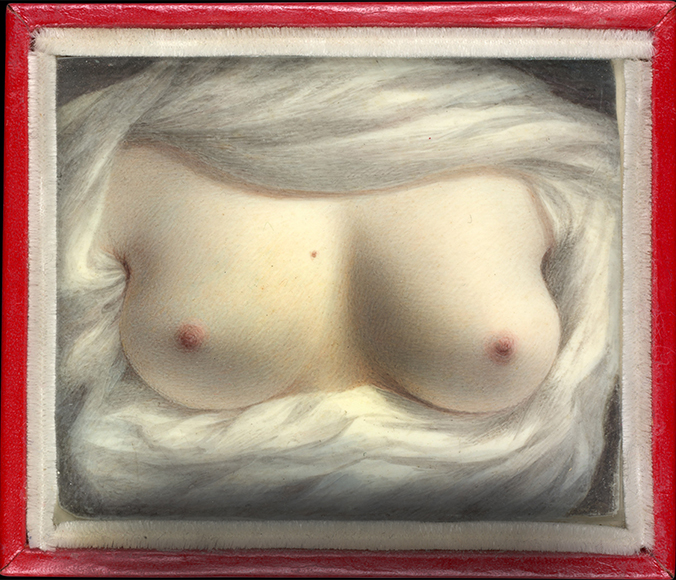

This extraordinary example of miniature art is certainly a lover’s token, and a scandalous one at that. It was created in 1828 by Boston artist Sarah Goodridge for Daniel Webster, a lawyer who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in Congress and served as secretary of state under three presidents.

The scandalous part is the subject matter, not an amorous eye but a pair of bare breasts — Sarah’s breasts. The subject matter would be considered daring under any circumstances, particularly since Goodridge and Webster were not married, or even engaged.

Despite her daring gesture, the recently bereaved Webster did not ask her to marry him. Instead he quickly chose a New York heiress to be the second Mrs. W. But the artist and the ambitious politician remained in touch for many years. Sarah never married. And when Webster died, the miniature, known as “Beauty Revealed,” was found among his personal belongings.

Lover’s eyes went out of fashion. In part they were superseded by the new technology of photography, which made images of loved ones readily available and inexpensive. Society became less restrictive and it was increasingly acceptable to display romantic feelings openly. Still, around 1,000 eye miniatures remain, as watchful reminders of a more discreet but no less passionate past.

For more, contact Katie at kwhittle@skinnerinc.com or 212-787-1114.