He was the dean of American letters at the young nation’s dawn, a writer admired by Edgar Allan Poe who mentored Walt Whitman and inspired the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to quote him in his speech “Give Us the Ballot”: “Truth crushed to earth will rise again.”

He was a mover and shaker about New York City, the co-owner and editor-in-chief of the influential New-York Evening Post (now simply the New York Post), who helped drive the creation of Central Park and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and whose political shift — from conservative to progressive — followed a trajectory that many American lives have taken.

He was a legend whose name is now attached to everything from the park behind the New York Public Library to schools in Long Island City, Milwaukee and Cleveland; a house at Williams College, which he attended briefly; one of the original villages of Columbia, Maryland; and a neighborhood in Seattle.

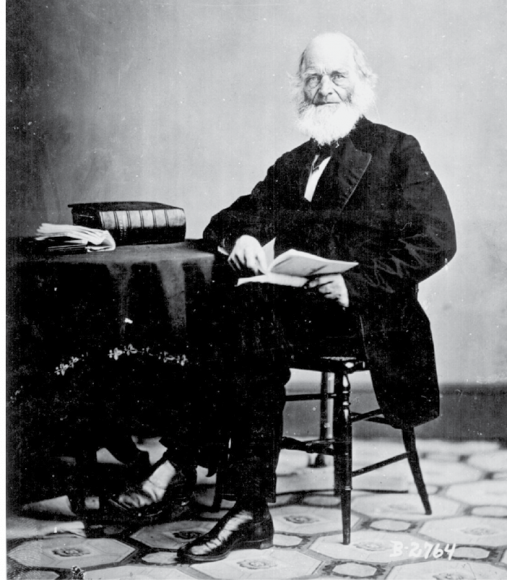

William Cullen Bryant (1794-1878) possessed a name that will also be on the lips of those attending New York Medical College’s virtual fundraising “Founder’s Dinner” on Oct. 21. (As leader of the civic group that created the college, now located in Valhalla, Bryant was interested not only in the quality of New York City’s hospitals but in an enlightened medical education that would transcend purges, bloodlettings and high doses of drugs.)

But he is perhaps best-known today as an editor and writer of poetry and prose who befriended the Hudson River School of 19th century landscape painting that portrayed the Americas, and the United States in particular, as the new Eden in the decades that bracketed the Civil War.

Writers have always championed artists, as in the case of critics like Clement Greenberg, who helped put the Abstract Expressionists on the map — and, by extension, make New York City the capital of the art world — in the postwar era. (Writers have on occasion also wielded a poison pen in response to art: The terms “Hudson River School” and “Impressionism” were meant to be derogatory references to works that were considered respectively old hat and lacking clarity.)

“Sometimes it’s not so much a direct one-on-one correlation, but in each era, there is the establishment of a style in writing or art,” says Bartholomew F. Bland, executive director of the Lehman College Art Gallery in the Bronx. “For Bryant and (Hudson River School founder Thomas) Cole, it was the soaring of the landscape, Romanticism with a capital ‘R’.”

And an abiding friendship in that landscape. Laura L. Vookles, chair, curatorial department, of the Hudson River Museum in Yonkers — whose ongoing “Landscape, Art & Virtual Travel” exhibit includes the two-volume, Bryant-edited “Picturesque America — points to Bryant’s 1829 “Sonnet to Cole — the Painter Departing for Europe,” which begins:

Thine eyes shall see the light of distant skies:

Yet, Cole! Thy heart shall bear to Europe’s strand

A living image of our own bright land,

Such as upon thy glorious canvas lies….

Translation: Cole, you may have been born in England, but don’t forget the land you have immortalized and the friends here who love you.

“Cole and Bryant shared a deep love of nature, which each in his own way extolled in poetry,” Barbara Ball Buff writes in “American Paradise: The World of the Hudson River School,” the catalog for a 1987 exhibit at The Metropolitan Museum of Art that remains a landmark in Hudson River School scholarship. “Their friendship included (Cole disciple Asher B.) Durand and extended to a lively correspondence, meetings at their clubs and at the (National) Academy (of Design) and…frequent treks together in the wilds of the Catskill, Adirondack and White mountains. (Bryant, who wrote frequently on art and reviewed the National Academy exhibits as editor of the New-York Evening Post, described in its pages those wilderness trips.)”

The three worked together on “The Talisman,” an 1827 Christmas gift book, and “American Landscape” (1830), which featured Bryant’s writings illustrated by Durand’s engravings of paintings by Cole, himself and others.

Durand would capture the trio’s bond poignantly in “Kindred Spirits,” an oil on canvas he painted in 1849 — the year after Cole’s untimely death — that depicts Bryant and Cole standing on a ledge overlooking the Catskills. It is a painting that considers not only nature but death itself as Bryant, hat in hand, listens respectfully to Cole, who takes his leave by gesturing with his paintbrush to the misty mountain clefts that recede to eternity.

For the Romantics, nature and death were intimates. In Bryant’s most famous poem, “Thanatopsis” (1811,’17,’ 21) — from the Greek, meaning “a view of death” — he writes that all in the end must:

Go forth, under the open sky, and list

To Nature’s teachings…. Earth, that nourished thee, shall claim

Thy growth, to be resolved to earth again,

And, lost each human trace, surrendering up

Thine individual being, shalt thou go

To mix for ever with the elements….

“Thanatopsis” — the inspiration for C.K. Wilde’s 2015 currency collage of the same name that was part of the Lehman College Art Gallery’s 2019 “Mediums of Exchange” exhibit — was written in Bryant’s New England youth. He was born and raised in Cummington, Massachusetts, the son of Peter Bryant, a doctor turned state legislator, and his wife, the former Sarah Snell, who traced her ancestry to Mayflower passengers John Alden and Priscilla Mullins, immortalized as part of a love triangle in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “The Courtship of Miles Standish.” (Bryant was also the nephew of Charity Bryant, a seamstress who lived in Vermont in a well-documented professional and personal relationship with Sylvie Drake of which family and community approved. As their affectionate nephew wrote of them: “If I were permitted to draw the veil of private life, I would briefly give you the singular, and to me interesting, story of two maiden ladies who dwell in this valley. I would tell you how, in their youthful days, they took each other as companions for life, and how this union, no less sacred to them than the tie of marriage, has subsisted, in uninterrupted harmony, for more than 40 years.”)

Despite his distinguished pedigree and early promise as a poet, Bryant did not come from a wealthy family, and he was forced to take up the law as a viable career, particularly once he married Frances Fairchild and moved to Great Barrington, Massachusetts.

The law, however, proved not to his liking and he gave it up in 1825 for the life of a journalist in New York, where he quickly advanced at the Post, founded by Alexander Hamilton. Bryant was an early proponent of conservative, Hamiltonian Federalism. But that too went by the wayside for a more progressive politics in editorials that supported immigrants, religious minorities and workers. (As an elector in the 1860 presidential election, Bryant voted for Abraham Lincoln.)

It is on his writings that Bryant’s reputation ultimately rests. Indeed, children’s author Mary Mapes Dodge (“Hans Brinker”) would say: “You will admire more and more, as you grow older, the noble poems of this great and good man.”

The New York Medical College Founder’s Dinner will begin at 5:30 p.m. on Oct. 21. For more, visit nymcalumni.org/foundersdinner.