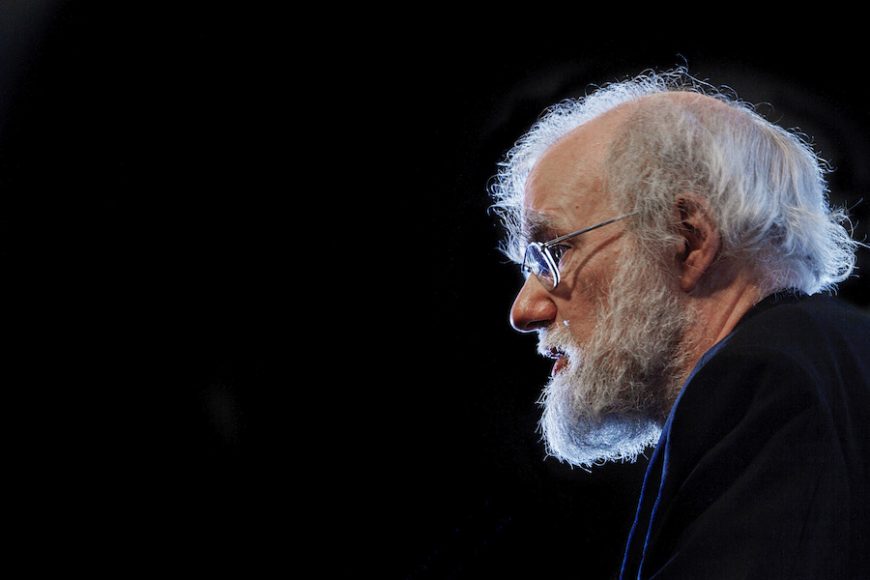

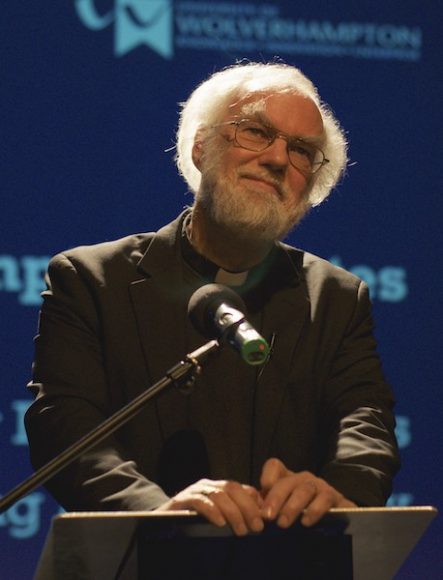

One of the most provocative yet playful descriptions of prayer ever offered was by Rowan Williams, the Welsh Anglican theologian who served as Archbishop of Canterbury from 2002 to 2012. Williams famously compared prayer to bird-watching, as both endeavors require endless patience and stillness while in pursuit of an often-elusive goal.

Williams acknowledged patience and stillness are rarely seen as virtues nowadays, especially in a digitally driven society where almost everyone has an activist opinion to share on social media soapboxes. However, in a Sept. 20 Zoom lecture offered to the parishioners of Christ Church Greenwich, Williams insisted patience and crusading are not antithetical.

“There’s no big gulf between what the Christian tradition calls contemplation and action – no big gulf between prayer and activism,” said Williams, who became Baron Williams of Oystermouth after being elevated to the House of Lords in 2013. “We act so that the world will change into something slightly better, reflecting the will of God. Of course, we need to take the risks and accept the disciplines of transforming action. And that is an intrinsic part of our Christian discipleship.

“But without the stillness,” he added, “without the dimension of careful watching, that action can suddenly become more and more anxious, hectic and paradoxical – and at the end of the day, self-serving. We need to step back to see a situation for what it is, a person for who they are, before we rush in with our activists’ solution. And that’s very hard, especially in a culture where instant reaction negative or positive, usually on Twitter, is so much a part of how we see our lives.”

For Williams, the balance between stillness and activity can be traced to the example offered through the Gospels.

“That’s what we see in Jesus, the Jesus who spends long solitary nights simply breathing in the gift of his father and who then goes out to act in a way that makes an unexpected, life-giving difference,” Williams observed. “If we can, ourselves, enter into something of that eternal rhythm, immersing ourselves in the silence and mystery of God’s love, being pushed further out by the very depth of that love into making a difference in the world, then our discipleship will indeed be authentic and true.”

During his 10 years as the spiritual leader of the Church of England, Williams sought to build bridges with other faith. He was the first Archbishop of Canterbury to attend a papal funeral following the 2010 death of Pope John Paul II and spoke forcefully against anti-Semitism and Islamophobia. His efforts to redefine the roles of women and openly gay men in Anglican leadership were initially considered controversial by many but are now widely seen as the first serious effort to bring the church into a 21st century concept of inclusion. He also spoke forcefully against the Iraq War, openly criticizing Prime Minister Tony Blair’s decision to have British forces join the President George W. Bush’s invasion and occupation.

In his presentation, Williams acknowledged that the commitment to activism comes with great risks. He cited Matthew 16:24: “Then Jesus said to his disciples, ‘Whoever wants to be my disciple must deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me’” – as an example, noting that Jesus was not referring to a hypothetical burden.

“For that age, the cross wasn’t just a metaphor for the religious ideals,” he explained. “It was a real, immediate, horrifying risk. It was the way criminals died. You have to take a risk – a risk that others won’t understand – or, maybe, even worse, that people will not just not understand but hate.”

And yet, Williams noted, that is where contemplative patience can bring order to chaotic emotions when the danger of activism becomes overwhelming.

“Don’t panic,” he continued. “Stay faithful, stay rooted. Because on the far side of all this, what you’re rooted in is the truth of God’s love – a truth which doesn’t depend on majority votes, which doesn’t depend on success.”

But Williams stressed that contemplative patience is not the same thing as intellectual passivity.

“On the contrary, the disciples in the Gospels certainly asked questions,” he stated. “And especially in Mark’s Gospel, they frequently asked rather stupid questions, which is very encouraging for the rest of us. They asked questions, they challenged, they don’t hold back. The disciples are not just sheep-like and passive. But the first thing they’re invited to do is to come and see, to be witnesses of, as we might put it, what it is that’s coming through or pushing up in the life of Jesus – something that is beginning in the world.”

For his own example, Williams admitted to be able to “keep a substantial time of physical stillness” after insight from Buddhist friends on using his body to adjust breath control for achieving physical and emotional serenity.

“Every morning, that’s where I start,” he said. “That’s what I try to do to orient myself for the day that’s coming. And like a lot of people, I will use a simple phrase to hold my mind to do what I’m doing. Like so many of these Orthodox Church, I will say, ‘Jesus Christ, have mercy on me.’ And just say that, as I breathe out every time, not necessarily saying it on my lips, but thinking those words, letting them come in a steady rhythm.”

While Williams acknowledged that this is not always the easiest of tasks, with distractions frequently interrupting concentration and doubts leaving a residue on your resolution, he insisted maintaining patience will ultimately offer the greatest payoff imaginable.

“The Gospels suggest spotting where the kingdom is breaking through is something that needs quite a lot of skill in being quiet and watching,” he said. “I’ve said quite often that it’s a little bit like bird-watching: Something wonderful is about to flash across your visual field. You don’t quite know when. But if you’re fidgeting, fussing and making noise, quietly focus on the landscape. And slowly, you see something opening up.”