I had been hearing about artist Jon deMartin for years, but although he is a near neighbor of mine in White Plains, we had never met. Sure, I had read about him. I knew he was regarded as one of the finest representative artists currently working, as well as a popular commercial artist and a gifted teacher. What I didn’t have him down for particularly though, was a thoroughly nice guy, the kind of guy you immediately want to call your friend.

A plan to meet hatched at last and DeMartin is there to greet me at the door of his studio. It’s a charmingly disordered fourth-floor atelier on North Pearl Street in Port Chester, where Hopperesque canvases, palettes, brushes and paints, easels, skeletons (the fake kind), mannequins, torso models and books galore seemed to be clamoring for space, and where I am immediately aware of the essential, natural light flooding in from towering, tall windows. Trim, well-proportioned and with what I instinctively feel is a sunny countenance behind his mask, in jeans and crew-neck over a white T-shirt, deMartin has as a 1950s, Beat Generation cool about him. Think Jack Kerouac or Neal Cassady. What he doesn’t have, I quickly discover, is any of the Beats’ self-absorption or preening arrogance. On the contrary, he is the very epitome of modesty, from the gracious emails he has written me ahead of our meeting, to his persistent insistence on how he is still learning (and how much more there is to learn) and the way he downplays his talent at every turn.

eMartin grew up in Wilmington, Delaware, but moved to Larchmont when he was about 10. His father was a designer. Just out of Pratt Institute, he had been hired by DuPont — recruited, deMartin tells me, by the great graphic designer, Sol Bass, best-known for his film-title sequences and his now iconic corporate logos. “I played baseball back then. I was a real jock,” deMartin says, only half-jokingly. Lean and fit in his mid-60s, I can quite see it.

He played baseball at Mamaroneck High School but always loved to draw. “I remember my dad having a very large art book, one of those coffee table books on Leonardo da Vinci and looking at it as a kid. It made an impact.”

After graduating high school, deMartin really wanted to pursue baseball and relocated to Miami to do so. But with nothing working out in that department after a couple of years, he enrolled, like his father, at Pratt Institute, graduating with a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree in filmmaking.

It was a hard road, however, to get to be a director of photography, and art was always beckoning. He also believed — and still does — that the ultimate creative freedom is art. “Right now, I’m doing more and more picture-making, which means I’m in control. Sometimes I’m the director and sometimes the actor,” he says with a laugh. Indeed, he is, appearing in any number of his own works, and no Hitchcock-like, cameo-appearance either, but center stage, bare-chested as the artist’s model or as the artist himself, brush in hand, a self-portrait of the artist at work.

Back to life after Pratt, though, and after 10 years working for his father as a graphic artist, he was asked to teach a drawing class at the New York Academy of Art, which was a kind of turning point. Further teaching jobs followed, at the Lyme Academy of Fine Arts in Old Lyme, Connecticut, at Studio Incamminati School for Contemporary Realist Art in Philadelphia and at the Parsons School of Design in Manhattan. He credits his own teacher, Michael Aviano — “my 92-year-old mentor,” as he calls him — with giving him the skills to be an effective teacher. “He had an ability to make things simple to understand. He kind of demystified classical art, which can be very complicated.”

DeMartin currently teaches at The Art Students League of New York in Manhattan and also privately. Prior to the pandemic, students would come to class in his studio in groups of six or seven, but for the time being he is teaching via Zoom. He also conducts trips abroad. Although Covid-19 put a Florence, Italy, workshop, under the auspices of BACAA (Bay Area Classical Artist Atelier,) this past summer on hold, he is hoping another trip next year, to paint in the atmospheric surroundings of the hugger-mugger Physic Garden in London’s Chelsea district, will go ahead.

Students, he tells me, run gamut although retirees make up a large number. At the risk of it sounding pejorative, he says, he describes his students as “serious hobbyists.” “Most have also always had a passion for fine art,” he says, “but first they had to make a living.”

I ask deMartin a “How long is a piece of string?” question, namely this: Coming to art relatively late in the day, how “good” can you hope to get? How long does it take to achieve some degree of competence?

“I think it depends how hard you work, what you put into it.” He quotes Hippocrates’ famous aphorism, best known in its Latin form: “Ars longa, vita brevis,” usually translated as “Art is long. Life is short,” which, of course, has many implications and interpretations. He also gives the example of a mutual friend of ours who, although only having picked up a paintbrush after a long and successful career in the law, has reached an exceptional level, winning prizes at art shows. “All because of the time and concentration she puts into it,” he says. In a reworking of the old joke about how you get to Carnegie Hall, the same would appear to be true of art: Practice, practice, practice.

A habitual, inveterate learner, deMartin is profoundly aware that there is always more to learn. For nine days every year for the last 10 years or so, he has taken himself to Venice, to spend time just looking at great works, understanding “construction” as demonstrated by Titian, Tintoretto and Ve-ronese, skipping over Venice’s ‘”lean” period of the 17th century and then picking up again with Canaletto and the Tiepolos.

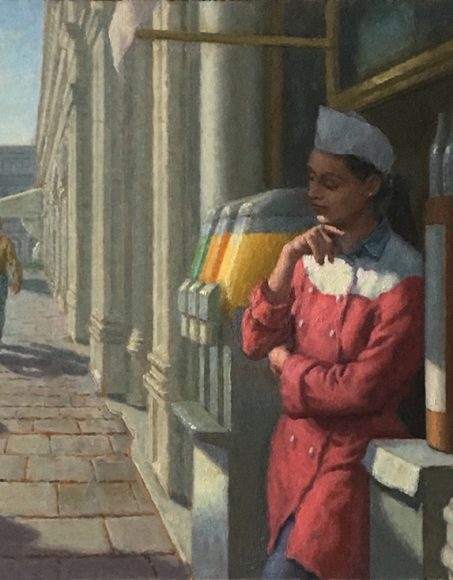

He says he doesn’t take commissions, because he likes the independence to choose his subjects, but concedes he has to stay in touch with the market and the sort of paintings people want to buy. (This means American subjects, he says.) Currently with the Cavalier Galleries in Greenwich, he shows me two nearly completed canvases that he will shortly send for sale. One is of a muscled worker pulling spikes on a graceful curve of railroad track, an industrial skyline in the background. (If this painting were set to music, it would be Giuseppe Verdi’s “Anvil Chorus” from “Il Trova-tore.”) The other is a steel bridge in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, the afternoon sun burnishing the hard steel with a golden hue, the man-made bridge contrasting with nature in an almost bucolic setting.

It is done entirely from memory or the imagination and, like all of deMartin’s paintings now, without the use of photographs. “A photograph doesn’t interpret nature,” he says, a twinkle in his eye, as I admire the work on the easel. “It just records nature. But a drawing, a drawing represents it.”

For more, visit jondemartin.com