During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, John Brewster Jr. was one of the most prominent portrait artists in the Northeast. And while he may not be a household name today, the quality and quantity of his work coupled with his extraordinary life experience make him one of the most intriguing figures in the development of American art.

Brewster was born in Hampton, Connecticut, in May 1766 — the exact date of his birth being uncertain. What is certain is that he came into the Colonial era with an extraordinary social advantage as the third son of John Brewster, M.D., a prominent member of the Connecticut General Assembly and a direct descendant of William Brewster, a Pilgrim leader who arrived on these shores via the Mayflower.

But Brewster’s birth also included what could have been a devastating difficulty for him in that time: He was born deaf and mute. His early years were mostly spent isolated from wider society, and he learned to communicate through pantomime with his immediate family and very few friends. His father’s wealth enabled him to receive private tutoring, including lessons by a local pastor named Rev. Joseph Steward on how to paint in the style of Ralph Earl, a prominent Colonial era portraitist. Being able to receive private art lessons was a luxury that few in Brewster’s time enjoyed.

“Most artists that did get training usually went to England to get it — like John Singleton Copley, Gilbert Stuart and Benjamin West,” says Elizabeth V. Warren, president of the American Folk Art Museum in Manhattan. “But the American-born artists, for the most part, were primarily either self-trained or got a little bit of training from other people who didn’t know much more than they did.”

Warren notes that despite the lack of formal training, these artists found themselves in a market where their services were highly in demand.

“There were lots of them,” she continues. “This was a time of a growing middle class. People had the money and the desire to have themselves represented to show how well they had done, or to have themselves remembered by their families. Remember, it wasn’t until the late 1840s when the daguerreotype comes to America that there was an alternative to having a portrait painted. So, there were quite a number of painters and they ranged in their skills from barely acceptable to quite proficient, as Brewster was.”

After initially painting portraits of relatives, Brewster’s family recognized his skills could make him financially independent. Ironically, the deafness that separated Brewster from his surroundings may have been the driving force in liberating his artistic talents.

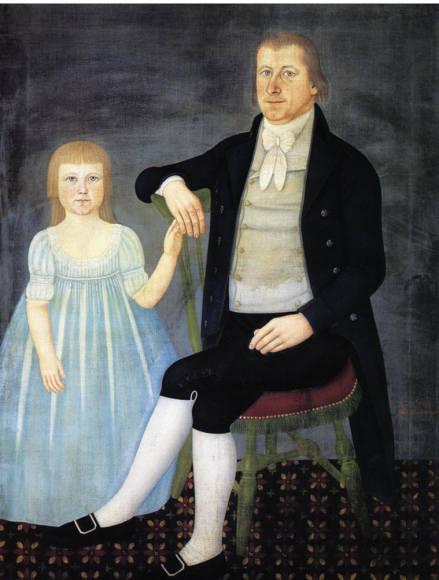

“Brewster focuses on the sitter’s face — the eyes, the expression — and he de-emphasizes the setting in the background,” says Paul D’Ambrosio, president and CEO of the Fenimore Art Museum in Cooperstown, New York. “When you look at the works of his peers, you don’t see what Brewster is able to see in his beautiful portraits. You see some nice likenesses, you see some beautiful designs and fluid brushwork, but you just don’t feel like you’re really gazing into somebody’s being. Brewster is making a profound connection with each sitter, and I think it can only be attributed to the heightened sense of visual awareness that comes with not having access to one other crucial sense.”

By his mid-20s, Brewster began advertising his portraiture services in newspapers while his family made inquiries within their social and professional connections to help him gain commissions. He moved in 1795 with his younger brother, Royal Brewster, M.D., to Buxton, Maine, though his career would take him throughout New England and eastern New York State, resulting in more than 250 portraits.

“Ralph Earl is known for taking the English style of portraiture and bringing it into America,” D’Ambrosio adds. “But Brewster was successful in simplifying it and making it popular in the countryside for ordinary people at an affordable price. So, he really spread portraiture throughout New England and he established a basic style that became prevalent by among self-taught artists in the Northeast.”

Brewster’s portraits of children were particularly beloved, with D’Ambrosio noting how “nobody quite painted children with such innocent beauty and purity as Brewster did. I don’t think he has a peer.”

One of these paintings, “Boy Holding a Book,” is part of the exhibition “Expanding Horizons: Celebrating 20 Years of the Hartford Steam Boiler Collection” that opens Nov. 7 at the Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme, Connecticut. Jennifer Stettler Parsons, the museum’s associate curator, says it is crucial to have Brewster as part of a presentation tracing the evolution of the American sociocultural experience.

“I think it’s really important when our society is thinking about ways to expand the narrative of history and move toward a more engaged social consciousness about our world,” she says. “And so many of those stories live in our historical work. John Brewster Jr. is a perfect example of that. This extraordinary artist was able to function as a deaf artist in a world where he was a minority and he didn’t have… methods of communication, so had to create his own.”

In 1817, at the peak of his career, the 51-year-old Brewster put his work on hold and traveled to Hartford to enroll in the newly opened Connecticut Asylum for the Education of Deaf and Dumb Persons, known today as the American School for the Deaf. And while the average age of his classmates was 19, Brewster studied for three years and learned to communicate in the then-evolving American Sign Language. Parson notes this was “the first time he found a community where he was able to identify with others.”

Brewster died in 1854 at the age of 88. Sadly, he did not leave a diary or memoir, so we are not certain how he viewed his place in the world. Nor is there any known image of him, which further separates his legacy from today’s consideration. But while the man’s inner soul and appearance remain mysterious, Warren praises him for creating an invaluable record of the people who were the backbone of the young America and who would have otherwise been lost to history.

“His patrons were not the elite people nor the wealthiest, but they were the professional middle-class farmers, doctors and lawyers,” she says, adding that Brewster’s celebration of these Americans deserves greater appreciation.

“For a long, long time, and in many places today, self-taught artists are still not considered worthy of our appreciation,” Warren says. “In my world, Brewster’s extremely well-known. But in the greater world, folk artists are rarely if ever taught in art history classes . They’re really dismissed as second-class citizens. And I think that’s wrong.”

For more, visit florencegriswoldmuseum.org.