For the quilting world, the pandemic period has been a Dickensian-

worthy best of times and worst of times. On one hand, individuals who found themselves moored at home during quarantine lockdowns brought a new passion and energy to their craft.

“With Covid, everyone started sewing, because we needed to make masks or we’re bored,” says Mary Watt, owner of the New Hartford retail store Quilted Ewe. “Or, we’re at home and we decide, ‘Let’s teach our children something that they can use later on.’ Not all school systems are offering homework or classes, so we can do something and make things together.”

Watt has also seen more newcomers to quilting finding her store.

“You can come in and buy a piece of fabric that’s preprinted and you just cut the items out,” she adds. “And you can make a pillow or a little quilt. That goes a little bit faster for the newbies.”

Mary Juillet-Paonessa, owner of CT Quilt Works in Mystic, has seen a stream of customers who’ve done extensive home inventories during the lockdowns and discovered long-forgotten quilts in need of restoration.

“They’re going through their house and finding things that their parents put away, and they remember the quilt pieces when they were younger and want them finished,” she says. “It’s a family heirloom that that they really want.”

On the other hand, the communal aspect of people joining together in quilting bees has been put on indefinite hold by the pandemic, severing an invaluable social connection for many.

Mary Ann Meils, president of Goodwives Quilters, a quilting guild based at the Rowayton Community Center, ruefully acknowledges her group has not met in person for more than a year because of the ongoing health crisis.

“We’ve been going for probably 35 to 40 years,” she says of her group. “We do a lot of charity work. We’ve done a lot of quilts for both Americares and Family and Children’s Services in Norwalk. We stay in touch, obviously, but we can’t get together. It’s just too dangerous at the moment.”

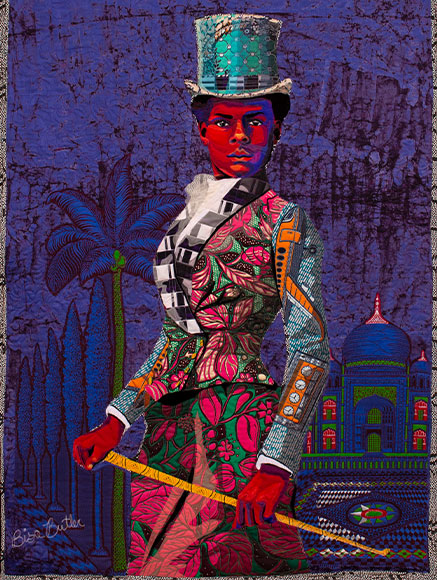

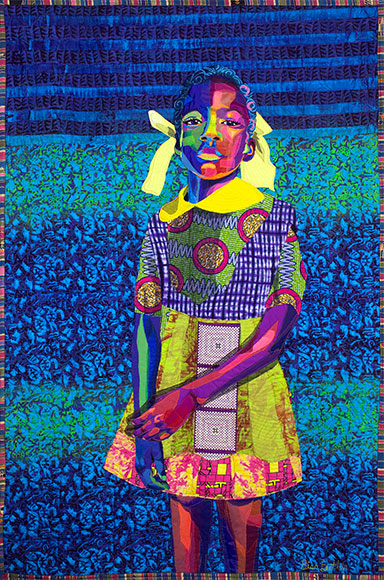

Also disrupted are the arts organizations that have worked to reinforce quilting’s place within the fine arts. Last March, the Katonah Museum of Art was set to open an exhibit of Bisa Butler’s mixed media creations that incorporated quilts into a celebration of Black culture, but the gala premiere never occurred because of state-mandated shutdowns. Still, Emily Handlin, associate curator of exhibitions and programs, says there was a happy ending of sorts when the exhibit finally opened as a virtual presentation last July and remained online through October.

“It ran a little longer than expected, which was wonderful because the reception was just more than we could ever have imagined,” she says. “It probably was our best-attended exhibition in quite a while. And in terms of the range of people we reached with the show, we brought in visitors from across the country and around the world. It couldn’t have been better.”

Quilting can trace its roots to ancient Egypt and the pursuit has occasionally turned up in unlikely historical connections, most notably when antislavery advocates hung quilts outside their homes that included coded messages to aid slaves escaping on Underground Railroad routes. In the 1990s, the AIDS Memorial Quilt forced the nation to acknowledge the devastation created by that pandemic.

“There was a major quilt revival in the 1970s at the time of the bicentennial,” says Pamela Weeks, curator at the New England Quilt Museum in Lowell, Massachusetts. “That’s also when many of today’s art quilters started doing their work.”

The pandemic struck the quilting world while it was at a curious crossroads. According to the Craft Industry Alliance, an industry trade group, the estimated size of the U.S. quilting market is $4.2 billion, with between 9 million and 11 million quilters. The demographics for this pursuit are nearly monolithic: The trade group estimates that 98% of quilters are female and 65% are retired.

But one thing that remains in flux is trying to define what contemporary quilting is all about.

“Some of it is folk art and some of it is fine art,” says Weeks. “And some of it are bed coverings.” That versatility is part of the genre’s attraction.

Frank Bennett, CEO of The National Quilt Museum, observes that visitors to his museum aren’t looking for bed coverings.

“Our visitors are art enthusiasts who go to art museums,” he says. “We have very, very high reviews on Tripadvisor, where we’re a Travelers ‘Choice winner.”

Bennett’s collection spans more than 650 quilts and features touring shows and rotating exhibitions. The aforementioned statistics on quilting demographics, he points out, include a growing number of teens and twentysomethings participating in youth quilting programs.

“There’s a misperception out there that quilting is a dying art form, when in reality quilting is a life cycle,” he says. “I’ll give you an example: There’s not that many 20-year-olds playing golf right now, but there’s a whole bunch of 65-year-olds playing golf right now. But you wouldn’t say golf is a dying sport since there’s not a lot of 20-year-olds that golf.

“It’s the same thing in quilting,” he adds. “The average person becomes a quilter after their kids go off to college and they’re looking for where their identity is going to go next. It’s just not a thing that that many young people do, not because they have any aversion to it but because that’s just not where they are in their life. They’re more focused on career building and having kids in that life cycle.”

But the New England Quilt Museum’s Pamela Weeks credits new generations as well as the Modern Quilt Guild, a global nonprofit with more than 15,000 members in 39 countries, with taking the quilting tradition in new directions.

“The modern quilters have developed another quilting revival,” she says. “And it’s a true movement. It’s a younger demographic with women in their 20s, 30s and 40s who are producing quilts that are art. It’s a very modern aesthetic and it’s wonderful.”

Still, quilters are not solitary beings and there is an energetic eagerness to put the pandemic in the rearview mirror and gather together again for their communal creativity.

“Everybody’s done a YouTube video on how to make different quilt & blocks and things, but there’s nothing like having the in-class, one-on-one help from a teacher,” says Quilted Ewe’s Mary Watt. “I have a large space that is about 3,500 square feet, which allows us to have at least 30 people in the shop, including our employees. We’re just waiting to open our doors to get everybody back in.”