Kathleen Gilje describes becoming an artist as “a whole, long process” in which “I had no choice” that began professionally with the restoration work that still informs her art.

Growing up in Brooklyn, she would watch her mother take time out from her housework to set up her easel, sit down and paint. At school, Gilje was the class artist. At City College of New York, from which she graduated in 1966, she majored in art and literature. Ultimately, her paintings would be shown everywhere from the Aldrich, Bruce and Katonah museums and what is now Hudson Valley MOCA to Manhattan galleries and European institutions. Still, she says, “I don’t know if at that time I thought I could make a living as an artist.”

A bold move

The die would be cast by an audacious lie. Gilje’s father had given her a trip to Italy as a graduation gift. Working her way north to south, she realized she didn’t want to leave the country but didn’t have the money to stay, and winter was setting in. Despite speaking “awful Italian,” she approached Antonio de Mata, a major conservator of Italian paintings in Rome, with a real whopper. “I said I’d like a job. I’m the conservator for The Metropolitan Museum in New York, and I was hired.”

It’s clear he didn’t believe her story as he put her to work sweeping floors and getting palettes together for $50 a week. And yet, this was totally in keeping with the traditions of art history, giving a fledgling an opportunity in an atelier to study with a master from the ground up.

“I had a good hand and soon I began restoring paintings,” she says of a career that took her from Naples back to New York. “So I thought, ‘I can make a living as a restorer. I don’t know if I can make a living as a painter.’”

And yet, her success with the former would be the springboard for the latter.

“At one point, I got an offer for an extraordinary job at a major museum,” she recalls of a moment in the late-’70s. “It would be a 100% commitment to conservation. That’s when I knew. I had heard about people who remained closeted artists. I didn’t want that.”

Working on the restoration of El Greco’s “The Fable” (1580, oil on canvas) for the art dealer Stanley Moss in the late-’80s, Gilje made an exact replica save for the playful addition of a light bulb that subtly underscored the painting’s firelit faces and El Greco’s chiaroscuro effects. Moss threatened to sue her, then offered to buy the copy. And that was the beginning of a career in which Gilje would recreate masterpieces by recasting female subjects in a heroic, activist light, drawing attention to their circumstances; and reclaiming the female body for themselves, herself and her female viewers.

In a sense, this has been a continuation of her work in restoration, for conservators, she says, often make changes in recapturing what has been lost.

“When I started to think how restorations were used,” she adds, “then I began to take on feminist subject matter.”

Women, restored

Gilje’s “La Donna Velata, Restored” (1995, oil on linen) gives Raphael’s “La Donna Velata” (1516, oil on canvas) a black eye in a commentary on domestic violence. Her “Le Violin d’Ingres, Restored” (1999) brings together Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’ “The Bather (The Valpinçon Bather)” (1808, oil on canvas) and Man Ray’s “Le Violin d’Ingres” (1924, gelatin silver print) in a work that adds the S-shaped sound holes of a violin and of Man Ray’s photo to the nude, violin-shaped back of Ingres’ odalisque. To some, the idea of a woman as an instrument may appear sexist, but when Gilje saw her work flanked by the original and Man Ray’s tongue-in-cheek takeoff in “Ingres et Les Modernes” at the Musée National des Beaux-Arts du Québec in 2010, “it was a thrill” that also proved to be a vindication for women portraying and viewing the female nude on their own terms.

One of Gilje’s most-traveled works captures the vulnerability of the female body in haunting terms. Her “Susanna and the Elders, Restored” (1998, oil on linen) and “Susanna and the Elders, Restored (X-ray)” (1998, of X-ray film on Plexiglas) retells the biblical story of a young Hebrew woman who is sexually blackmailed by two old lechers and of Artemisia Gentileschi’s “Susanna and the Elders” (1610, oil on canvas). Gentileschi — whose paintings have enjoyed a renaissance since the 1970s, with an exhibit at London’s National Gallery, the first major solo show of her work, available online — created her “Susanna” a year before she was raped and tortured at the subsequent trial to ensure she was telling the truth. Long fascinated by Gentileschi’s work and story, Gilje gives us a faithful representation of the former’s “Susanna” and an alternative X-ray pentimento — Susanna screaming and clutching a knife in a kind of self-defensive exorcism. (In the trial transcript, Gentileschi describes subsequently threatening her attacker, the painter Agostino Tassi, with a knife and then throwing it at him.) Gilje’s “Susanna” is in the collection of Phillips Academy’s Addison Gallery of Art, but she made an ink-jet print of her X-ray “Susanna” for “The Un-Heroic Act: Representations of Rape in Contemporary Women’s Art in the U.S.” at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice in 2018. The work itself will be part of “Susanna: From Mannerism to #Me Too” at the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum & Fondation Corboud in Cologne, Germany in 2022.

Though these works are more about personal stories than abstract movements for Gilje, they are often mentioned as examples of “the female gaze” in art. (See also the story on Fay Ku on Page 20.) But what is that gaze? Is any work — a landscape for instance, done by a woman — the result of a female gaze? Or is it more a response to “the male gaze,” as defined by feminist film critic Laura Mulvey, that has objectified women for centuries in the visual arts?

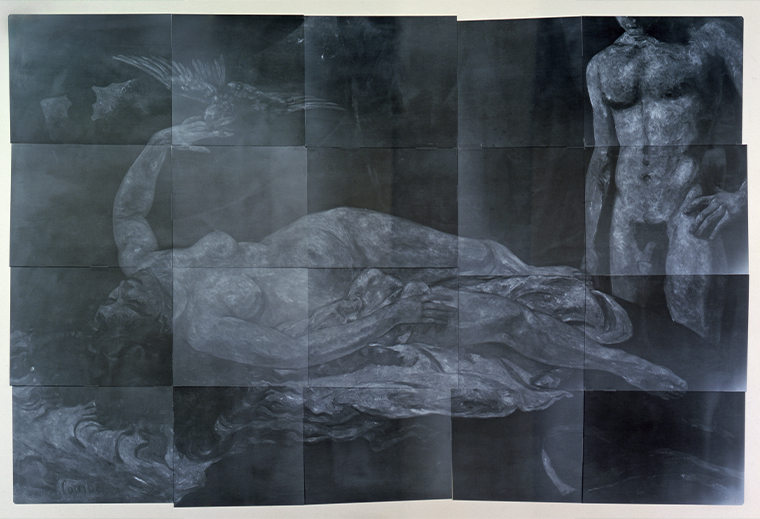

Gilje points to “In the Cut: The Male Body in Feminist Art,” a 2018 show at the Stadtgalerie Saarbrucken in Saarbrucken, Germany, that included her X-ray treatment of Gustave Courbet’s “Woman With a Parrot” (1866, oil on canvas), a female nude in The Metropolitan Museum of Art collection made all the more erotic by her limbs akimbo and the bird perched on one finger.

In Gilje’s version, however, it’s hard to concentrate on the woman because she has added a rippling male nude approaching the subject’s bed. In reclaiming the female body, women artists are also claiming their right to depict the male one.

“That exhibit was really about the female gaze,” she says.

For more, visit kathleengilje.com.