Lighting is one area of the auction business that has always intrigued me — specifically the large sums of money achieved at auction — whether it’s a six-figure Tiffany lamp or Georg Jensen silver chandelier or a pair of triton-riding marble turtle lamps that fetched nearly $30,000. Many designers have turned their creative powers to lighting design. But what of those designers who focused exclusively or primarily on lighting? Gino Sarfatti of Arteluce and Angelo Lelii of Arredoluce were Italian lighting designers and manufacturers who flourished during Italy’s postwar design boom. They are celebrated for their iconic designs and both firms have been the subjects of recent monographs. A number of their designs are still in production and vintage models are highly collectible today. While collectors can expect to pay large sums for the period works, newer examples are accessible at a fraction of the period pieces.

Venetian-born Gino Sarfatti (1912-1985) built one of Italy’s most important firms for modern architectural lighting design. Like so many of his peers, his path was shaped by the war years. Sarfatti studied aeronautical engineering until his education was curtailed by the failure of his father’s business, a victim of prewar sanctions. Sarfatti moved to Milan, working first for the lighting company Lumen and then striking out on his own, founding Arteluce in 1939. During World War II, he fled to Switzerland, because of his Jewish heritage.

Postwar, Sarfatti returned to Milan where his stylish retail shop and his lighting designs gained international attention. His designs were widely published and awarded honors at the Milan Triennials, the highly influential art and design exhibitions.

Sarfatti’s firm also commissioned lighting from preeminent Italian designers. The firm expanded to encompass wholesale and large-scale lighting projects, such as lighting for postwar Italian luxury ocean liners and Turin’s Teatro Regio, where his cumulus cloud installation consisted of hundreds of Plexiglas pipes. Sarfatti retired in 1973, selling Arteluce to the Italian lighting firm Flos, which still produces a number of Sarfatti designs today.

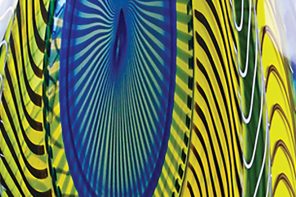

Early Sarffati works focused on directional lighting that was used to create a mood in a room or fulfill a specific lighting task. Sarfatti’s innovations leveraged new technologies to expand the scope of his designs, such as the use of Plexiglas or new lighting sources like halogen.

Sarfatti’s designs were referred to by number. Model 1063 was a floor lamp designed in 1954 and is now part of The Museum of Modern Art’s permanent collection. Minimalist in its design, Model 1063 featured a slender rectangular box that highlighted the then-novel fluorescent tubular bulb. Model 2097, a chandelier designed in 1958, broke down the centuries-old form to its essential parts. The chandelier features bare individual lights that are linked by an exposed electrical cord. The swaged cord cleverly mimics the traditional chandelier shape.

Angelo Lelii (1915—1987) was born in the Adriatic coastal town of Ancona and founded the firm Arredoluce in 1943 in Monza, northeast of Milan. Lelii’s career had a number of parallels to Sarfatti’s.

Lelii not only produced his own designs, but collaborated with other designers, most notably Gio Ponti and Etorre Sottsass Jr. The firm was a regular exhibitor at the Milan Triennials and Lelii’s works were featured in the cinema of the day, including “Roman Holiday” (1953). The firm gained lucrative lighting commissions from hotels throughout Italy and the Middle and Far East while also distributing its products in the United States. Lelii’s involvement in the business began to wane in the 1970s and the firm gradually retrenched until activity ceased in 1994.

Lelii’s best-known design is the floor lamp Model 12128, first exhibited at the 1947 Milan Triennale. Now known as the Triennale lamp, it was widely imitated and has become an icon of ’50s lighting design. The lamp featured three adjustable colored cones in primary hues (apparently in a nod to painter Piet Mondrian) on a tripod base. Later versions included monochrome cones and a marble base. Today, examples with colored cones and tripod bases are the most desired by collectors.

Truly sculptural in form is Lelii’s 1962 “Il Cobra” table lamp, Model 12919, which like many other iconic designs was sketched on a napkin during a transatlantic flight. The polished brass lamp featured a central magnetized sphere that focused an adjustable light beam with great precision. It was also one of the first usages of low voltage for a lamp, achieved by embedding a transformer in its base.

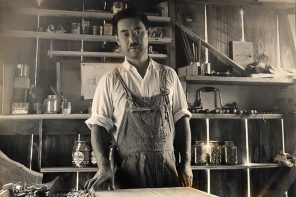

According to Jad Attal, Rago Auction’s modern design specialist, Sarfatti’s and Lelii’s works are so appealing because their designs were novel, clever, contraption-like and employed the most modern technology of the era. Yet these pieces also reflected impeccable workmanship, one of the great traditions of Italian craftsmanship. Their lamps were highly “machined,” that is, wrought by skilled workmen. So while uniform in design, the lamps exhibit the slight irregularities indicative of their individualized production.

For further reading, check out Anty Pansera et al.’s “Arredoluce: Catalogue Raisonne,” (2018); and Marco Romanelli and Sandra Severi’s “Gino Sarfatti: Selected Works 1938-1973,” (2012).

Jennifer Pitman writes about the jewelry, fine art and modern design she encounters as Rago Auction’s senior account manager for Westchester and Connecticut. For more, contactjenny@ragoarts.com or 917-745-2730.