It is at once a symbol of isolation and freedom, grit and glamour, boredom and adventure, heartache and hope, tragedy and transcendence.

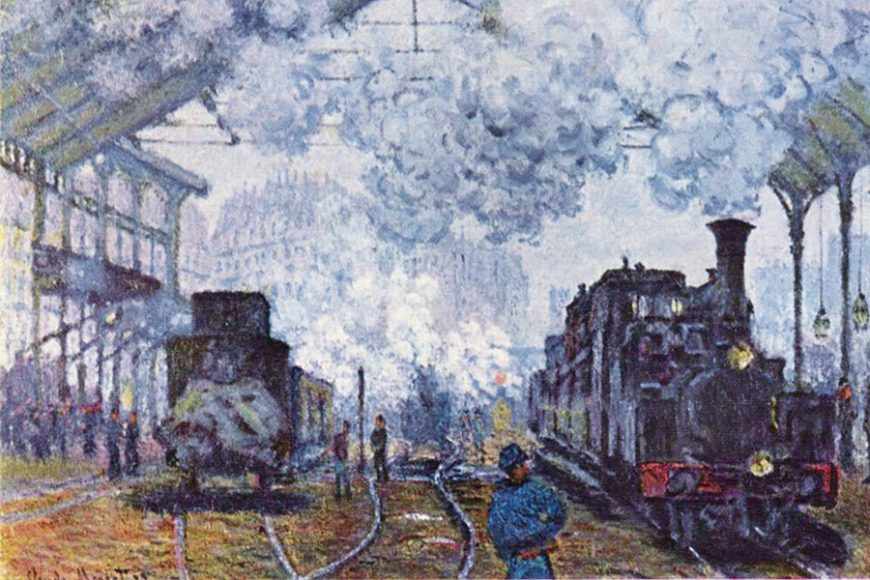

Perhaps more than any other mode of transportation, the train carries us from the past to the future along a present that can change with every twist and turn on the line. No wonder that the railway has been such a protean subject for artists, who find in it the serpentine conveyance of wondrous, terrifying possibilities.

The whistle blowing, the chugging rhythm of the wheels, the crescendo of the train’s approach and the diminuendo of it receding: The railroad represents freedom, even for those who don’t have a price of a ticket. Think of all those vagabonds riding the freight cars of the Great Depression, memorialized in Woody Guthrie songs and films like Martin Scorsese’s “Boxcar Bertha” (1972). Or the troubled Cal Trask in Elia Kazan’s film of John Steinbeck’s “East of Eden” riding atop a freight train, wrapped in a pullover in place of parental love, as he straddles the wholesome rigidity of his father’s farm in Salinas, California, and the bawdy brutality of his mother’s brothel in neighboring Monterey.

It’s no surprise then that the system of escape routes and safe houses that brought slaves to the North and freedom in the antebellum era was known as the Underground Railroad, brought to life in the new film “Harriet,” about former slave turned abolitionist and political activist Harriet Tubman.

Of course, the freedom of the rails is often most apparent to those who experience it from a distance, like the Johnny Cash of the song “Folsom Prison Blues,” who contrasts being stuck in prison with the sound of a train “rollin’ on down to San Antone.” But one person’s promise of freedom is a kind of isolation, even lonesomeness and confinement, for others. Those haunting paintings by Nyack’s Edward Hopper of passengers, railcars and signal houses that are solitary to the point of airlessness convey a loneliness beyond longing.

The confinement of the train and its accompanying stations and terminals — with their concealing compartments and cubbyholes — offer the opportunity for self-discovery (Wes Anderson’s loopy comedy-drama “The Darjeeling Limited”); and romance (the films “Twentieth Century,” “Brief Encounter,” “The Clock,” “Falling in Love”); but also an intrigue that can be amorous (“North by Northwest”) or lethal (“Murder on the Orient Express,” “Strangers on a Train”).

It’s hard for us to remember and thus understand now, but the train — whose advent standardized time in the first half of the 19th century — was once the new-fangled, suspect symbol of the future, offering a progress that brought death to a certain rural way of life and its proponents. The train was the ironclad snake in the new, American Eden of Hudson River School founder Thomas Cole, who wrote of his despair in trees being felled to make way for the Canajoharie and Catskill Railroad in his beloved Catskill, New York. A century later, trains would serve as the transport of the slaughterhouse not just for animals, but for humans, as any number of Holocaust films attest.

And yet, the railroad remains the stuff of nostalgic dreams, perhaps never better expressed than in Steve Goodman’s “City of New Orleans,” most famously recorded by Arlo Guthrie. As the singer rides “the train they call the City of New Orleans,” he journeys not just from Chicago to New Orleans on what was the longest daylight run in the United States, but from a rusted past through a fast-disappearing present in which “the sons of Pullman porters and the sons of engineers ride their fathers’ magic carpets made of steam.”

But the railroad didn’t go the way of all flesh. It went the way of radio — specializing to survive and thrive. The City of New Orleans still makes its way South with more of a streak than a rumble as part of Amtrak’s overnight service. And bespoke luxury tour company Ariodante is launching a series of 1920s-style murder mystery parties aboard the original Orient Express beginning in January. (Today the

Venice-Simplon Orient Express operates a

variety of routes using 1920s and ’30s cars, including the original Paris-Istanbul route.)

The magic carpet rides on.