“Why have there been no great women artists?”

It’s a question that feminist art historian Linda Nochlin posed in a seminal 1971 essay and answered in the illuminating 1976-77 exhibit “Women Artists: 1550-1950,” which she curated with Ann Sutherland Harris. (The answer, it turns out, was that there have been great women artists. They just lacked the opportunities for education and public advancement.)

The good news is that we needn’t pose that question any longer. ArtsWestchester’s exhibit “SHE: Deconstructing Female Identity” is among the most recent to demonstrate brilliantly that women artists do not lack an audience, even if they still lag behind men in terms of New York gallery shows, solo museum exhibits, directorships of the big museums and entries in tomes like H.W. Janson’s “History of Art,” according to the National Museum of Women in the Arts’ website.

The bad news isn’t just that women still have the proverbial long way to go; it’s that so much of their art continues to be focused on a painful relationship with the female body. Given the body-shaming issues that have riled the presidential campaign and debates, it’s no surprise. And it’s part of what make “Her Crowd: New Art by Women From Our Neighbors’ Private Collections,” at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich through Dec. 31, so provocatively topical.

The Bruce did not set out to make a show solely about women artists. It’s just that in selecting the works from private area collections, adjunct curator Kenneth E. Silver and Mia Laufer, the Bruce’s Zvi Grunberg resident fellow, were most drawn to works that happened to be by women, a museum spokeswoman said. How heartening is that? It’s in keeping what’s happening in other professions. The heads of the United Kingdom, Scotland, Germany, the International Monetary Fund and the Federal Reserve are all women. And Hillary Clinton, the first American female presidential candidate from a major party, may soon join them.

Women dominate colleges and graduate schools. They are increasingly the primary breadwinners in the United States — a trend that may continue now that we moved from a manufacturing to an information-based, service-oriented economy that plays to women’s wheelhouse.

The current century and millennium, then, are shaping up to be the century and millennium of women. So why do they still feel so bad about their bodies?

It’s telling that the exhibit opens with a work about a controversial female leader, Eva Perón, who was betrayed by her body in a most female way. (She died of cervical cancer in 1952.) Argentine artist Nicola Costantino’s 2013 photo/object “Eva: Los Sueños (The Dreams)” imagines Costantino as five Evitas arrayed on a sofa in a Cindy Sherman-ish triptych, complete with handmade gilded frame. In the center is glam Evita in severe blond chignon, choker and strapless white ball gown. She’s flanked by two businesslike Evitas in Chanel-type suits. On the far left, is hungry, on-the-make Evita, the poor villager-turned-Buenos Aires opportunist. But on the far right is sick Evita in a white gown, her hair undone, her inward gaze signaling a woman lost in thought — lost to the world.

“Females carry the marks, language and nuances of their culture more than (males),” Kenya’s Wangechi Mutu has said. “Anything that is desired or despised is always placed on the female body.”

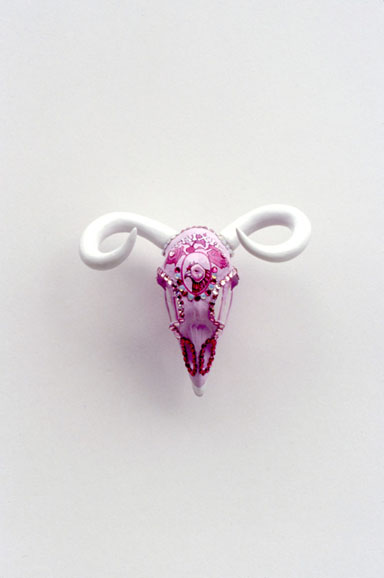

Her contribution is “Untitled (from ‘Tumors’ series), a 2004 work made of ink, acrylic, photo collage and contact paper on Mylar that depicts a cluster of pearlescent tumors from which chorus-girl legs in high heels sprout. It’s like a deliberately grotesque Busby Burkeley musical. E.V. Day’s “Satellite of Modern Love” (2016) follows that train of thought with a spidery sculpture made of Barbie-like arms and legs of resin, pure pigment and polymer on a steel stand. The cobalt color is patented International Klein Blue, which French artist Yves Klein once used in a performance art piece that involved naked woman lying down in the paint and pressing their bodies to a blank canvas. Another inspiration was an Uma Thurman poster in which her limbs appear distorted by elongation.

“Day,” the accompanying “Her Crowd” catalog notes, “combines these different instances — from canonized modern artists to contemporary entertainment — where female bodies are pushed to the breaking point.”

Pushing them further — race and ethnicity. In Betye Saar’s “The Weight of Color” (2007), an effective mixed media assemblage, a smiling Mammy figurine sits atop a bird cage in which a too-large black bird is cruelly contained, one foot outside an open door that is not big enough to let the bird escape. Add “Black Lives Matter” to a layer of overtones that include Jim Crow, Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Raven” and Maya Angelou’s “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.” In “Les Femmes du Maroc #16” (2005) by Morocco’s Lalia Essaydi, the cage is the henna calligraphy that covers the face, hands, feet and clothing of a figure that reclines sensuously like a 19th-century odalisque.

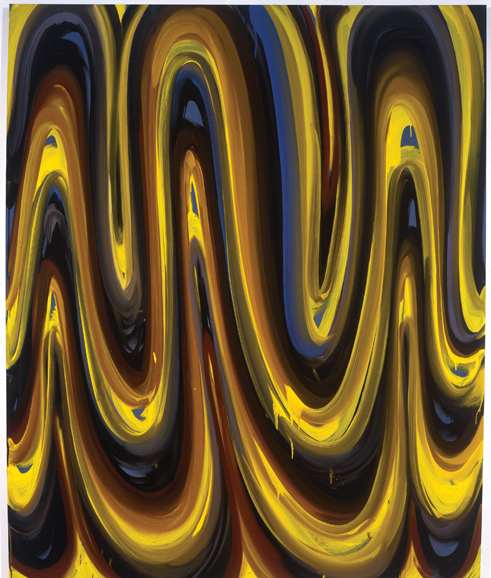

Even sainted motherhood offers no solace. In “The Mothers” (2011), an oil and charcoal on canvas, the United Kingdom’s Jenny Saville does a modern riff on the Renaissance Madonna as an exhausted mother struggles to contain two squirming infants. Nor does abstraction — and the trend away from figurative art — suggest respite. New York native Tara Donovan’s “Untitled (Pins)” (2004) is a Minimalist cube made of tons of straight pins, symbol of feminine domesticity. It looks painful.

Perhaps one of the reasons the female body is so fraught, so laden by our culture is that women remain its primary sex symbol. Hilary Harkness’ “Blue Nude” (2012-14), a lesbian empowerment painting, continues the objectification by featuring in the backdrop “Blue Nude” and “Two Tahitian Women” by Henri Matisse and Paul Gauguin, respectively, who, according to the catalog, “reduced women to primitive icons of sexual fantasy.”

Perhaps the answer to female body issues is to reconsider the male as the not-so-obscure object of desire. The most amusing work in the show is Malia Jensen’s bronze sculpture “Young Bucks” (2010), in which two male deer mate. Think “Animal Kingdom” meets “Brokeback Mountain.”

By concentrating more on men as sex symbols we might one day have a world with fewer comments like the one about a “disgusting” overweight beauty queen made by a male candidate who is — let’s face it — no Apollo Belvedere.

For more, visit brucemuseum.org.