“Fish and visitors stink after three days,” Benjamin Franklin penned in “Poor Richard’s Almanack.” How well this Founding Father understood the paradox of hospitality: To offer it is to engage with the divine and yet, for host and guest alike, it can be a hellish challenge.

Perhaps this is why every major religion and mythology has put such a premium on it. To the ancient Greeks, Hebrews and Asian Indians, hospitality was a responsibility inspired by divinity itself. Jesus takes the concept one better, extending it beyond the guest — who is, after all, generally known to you — to the stranger, as in the story of the Good Samaritan, who cares for a robbed, beaten traveler left for dead on the side of the road and puts him up at an inn. This is hospitality in its purest form — the word is from the Latin hospes, meaning “host,” “guest” or “stranger” — with no expectation of reward. But sometimes — OK, oftentimes — the host may have an ulterior motive, such as the desire to show off or extract a favor from the guest, which almost always backfires. In “The Man Who Came to Dinner,” George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart’s 1939 comedy, a starstruck industrialist invites radio personality Sheridan Whiteside to his Ohio home one evening before Christmas only to have the imperious “Sherry” take over the place for a month when he slips on the ice outside and injures his hip. (Kaufman and Hart got the idea when critic Alexander Woollcott — who’s name was always preceded by the qualifier “acerbic” — showed up at Hart’s Bucks County, Pennsylvania, estate unannounced one day and proceeded to terrorize the place, exiting with this guestbook sign-off: “This is to certify that I had one of the most unpleasant times I ever spent.”)

The play, made into a 1942 film, has an ironic O. Henry ending: Just as Sherry is healed and all his mischief put to rights, he falls again and is carried back into the house screaming. That’ll teach you to entertain celebrities.

“The Man Who Came to Dinner” is the kind of madcap, escapist story about the minute problems of rich people that filmgoers flocked to during the Great Depression and World War II. While its tale of a guest holding his hosts hostage emotionally is played for laughs, stories of guests held hostage have proved more poignant and even tragic. Belle in the various incarnations of “Beauty and the Beast” — especially the superb Walt Disney animated musical, Broadway show and live-action film — is really the Beast’s prisoner. She doesn’t become his guest and, ultimately, his bride and hostess until they fall in love.

The opera star and Japanese industrialist who are drawn together in “Bel Canto,” a 2001 novel by Sarah Lawrence College graduate Ann Patchett, have no such luck. They are brought together at a birthday party for the opera-loving industrialist, thrown by the vice president of an unspecified South American nation, who hopes to get the industrialist to invest in his country. (Patchett based the book — which has inspired a 2015 opera and a film that will be released in September — on the Japanese Embassy hostage crisis in Lima, Peru, a four-month standoff in 1996-97 that left one hostage, two commandos and 14 militants dead.) In Patchett’s story, lives are lost, too, but new, unexpected alliances are also made.

Sometimes, the guests are hostages of themselves and their own complacency. In “The Exterminating Angel” — Luis Buñuel’s Surrealist 1962 allegory of the dangers of being too comfortable, particularly in a totalitarian society — the guests find that they cannot leave the lavish dinner party to which they’ve been invited. It’s only after they think about their actions and reconstruct the past that they can leave — only to discover others are trapped outside in different ways. The story is retold in Thomas Adès’ opera, which received its American premiere at The Metropolitan Opera last fall.

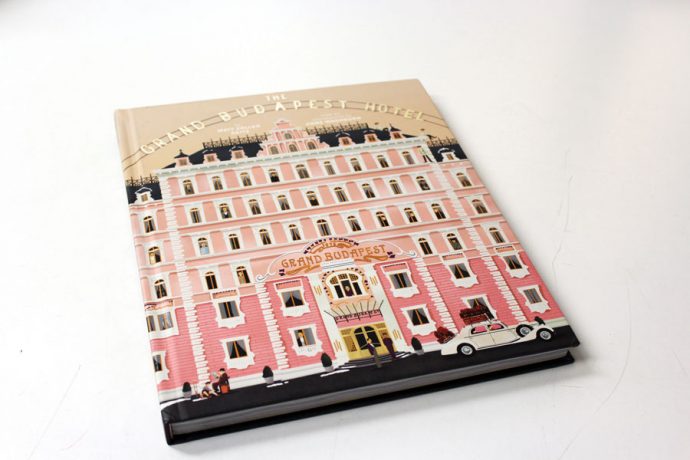

Is it easier perhaps to be a host and a guest when it’s clearly a business transaction, as in the hospitality industry? Maybe — but then again, given all the horror stories from travelers, maybe not. These certainly make for some grand movies, though, none grander than Wes Anderson’s profound, loopy “The Grand Budapest Hotel” (2014), which features what may be Ralph Fiennes’ most brilliant performance to date. In a film that is a series of narrative Russian nesting dolls — a story within a story within a story — set amid the uneasy splendor of Central Europe in the period between the two World Wars, Fiennes stars as M. (for Monsieur) Gustave, the concierge of the titular hotel. Part taste-making autocrat, part wily servant — and, in the end, a poignantly unexpected protector — M. Gustave attends to every need of his guests, which includes often visiting wealthy, elderly blond ladies in their suites at night.

By day, he instructs the staff, including his faithful Lobby Boy, Zero (the marvelously deadpan Tony Revolori) in the hotel’s more legitimate services. Part of the fun of the movie is watching Zero scurry back and forth across the confection of a hotel lobby, carrying suitcases, chairs and dogs, ever mindful of M. Gustave’s instructive running commentary — to such an extent that in the end, Zero really becomes M. Gustave, or at least a more obviously understanding version of him.

The film then is transformed, too, into a metaphor for the wondrous mysteries of mentorship in how to be a host to others. And it’s a reminder that if the mentor is beloved enough and the protégé an apt enough pupil, he may inherit if not the keys of the kingdom then at least those behind the front desk.