If Orson Welles’ “Citizen Kane” (1941) is considered one of the best films ever made, then his follow-up, “The Magnificent Ambersons,” can be regarded as his spectacular “what if.”

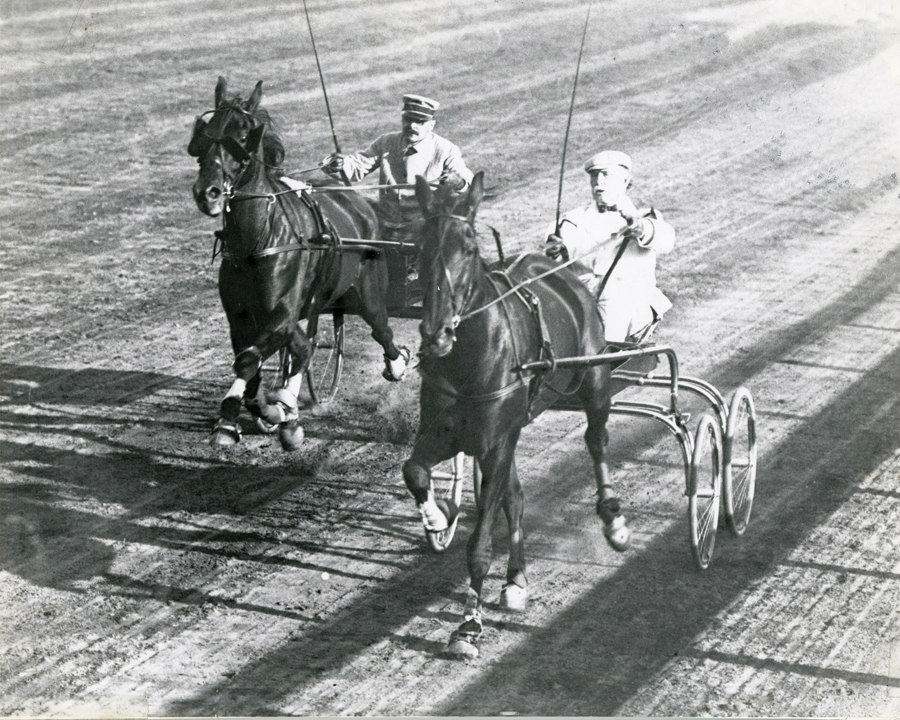

The movie – based on Booth Tarkington’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 1918 novel about a great American family’s reversal of fortune as America herself segued from the horse-and-buggy era to an automotive culture – was cut and re-edited without Welles’ approval. It would become in the minds of some Hollywood critics a metaphor for Welles’ own trajectory from boy wonder to difficult has-been.

When production commenced on “The Magnificent Ambersons” at RKO in Los Angeles in the autumn of 1941, Welles was still the enfant terrible who had held a nation spellbound with his 1938 “War of the Worlds” radio broadcast and dazzled critics (if not the box office) with the haunting, controversial “Citizen Kane.”

Welles constructed an actual house – albeit one with removable walls so the camera could roam its rooms – and filled it with actors from The Mercury Theatre like Joseph Cotten, Agnes Moorehead, Anne Baxter and Ray Collins to tell the story of a proud, affluent family in turn-of-the-20th-century Indianapolis brought low by the rise of the newfangled automobile.

But the catalyst for the Ambersons’ ruin is scion George Amberson Minafer (Tim Holt), the spoiled, clueless son of the doting Isabel (Dolores Costello), who had loved but rejected the ambitious Eugene Morgan (Joseph Cotten). When the widowed Eugene, a successful auto manufacturer, returns to town 20 years later with lovely daughter Lucy (Anne Baxter) in tow, George courts her while vowing to keep Eugene away from his mother. (In this he is spurred by his spiteful Aunt Fanny, played by Agnes Moorehead, who fancies Eugene for herself.)

In a key scene, George tries to discredit Eugene by describing the automobile as a “useless nuisance.” Eugene doesn’t disagree, adding that the automobile is going to change civilization – and not necessarily for the better. Here you have to wonder how much Welles the screenwriter drew on his own Midwestern background as the son of the successful inventor of a bicycle lamp, who became an alcoholic and went bust.

“You see, the basic intention was to portray a golden world – almost one of memory – and then show what it turns into,” Welles would tell director Peter Bogdanovich in a series of conversations (1969-75) that make up the book “This Is Orson Welles.” “Having set up this dream town of the ‘good old days,’ the whole point was to show the automobile wrecking it – not only the family but the town.”

To conjure this “golden world of memory,” Welles sought out cinematographer Gregg Toland, who contributed immeasurably to the chiaroscuro of “Citizen Kane.” When he proved unavailable, Welles hired the meticulous Stanley Cortez to create the shadowy, elegiac atmosphere of “Ambersons.” Together, they devised the continuous crane shot that sweeps up the stairs of the mansion to the third-floor ballroom.

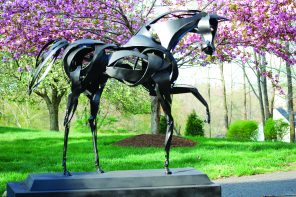

Cast and crew repaired to the Union Ice Co., an icehouse in downtown L.A., for the nostalgic scene in which Welles juxtaposes a sleigh ride out of Currier and Ives – complete with sleigh bells – with one in a horseless carriage. (Sleighing would hold a similar nostalgia for Welles in “Citizen Kane.” Rosebud, anyone?)

Welles would playfully reference “Kane” in “Ambersons” by including a story on an increase in auto accidents on the front page of the Indianapolis Daily Inquirer, one of the newspapers owned by the fictional Charles Foster Kane. The front page contains the Stage News column written by critic Jed Leland (played in “Kane” by Joseph Cotten.)

It was all punctuated by a score by Bernard Herrmann, who would later provide the irresistible undertow in some of Alfred Hitchcock’s most haunting films, including “Vertigo.”

But perhaps Welles didn’t pay enough attention to his own script or Tarkington’s novel, for “Ambersons” isn’t just a lament for the horse-and-buggy days. It’s the cautionary tale of a family done in by its own inability to adapt to changing times. In a sense, George’s lack of self-awareness would mirror Welles’ own. In renegotiating his contract with RKO, Welles had given up his right to the final cut of “Ambersons.” That would prove a critical mistake when Welles took off for South America to make a good-neighbor wartime documentary at the behest of Nelson A. Rockefeller.

Back home, RKO was busy cutting 40 minutes from the film, which had not tested well with a preview audience, and reshooting the ending. The studio shortened the long, seamless shot leading up to the ballroom – in which the viewer feels as if he’s a guest making his way from room to room at the Amberson mansion; softened the self-centered Ambersons; and created a happier ending in keeping with Tarkington’s novel.

In the rough cut, George wanders disoriented around an increasingly industrialized city and is hit by an auto – so ironic, or maybe just so fitting. In the film’s final scene, Eugene visits the forlorn Fanny in a boardinghouse to tell her he has reconciled with the injured George and in so doing, was “true at last to my true love” – George’s departed mother, Isabel. In the final cut, Eugene and Fanny leave the hospital together after seeing George. Fanny smiles as Eugene notes that in reconciling with George, he was “true at last to my true love.”

Ironically, Welles had offered to provide a happy ending with closing credits that showed the Ambersons in their golden youth and George and Lucy driving off together. But it was not to be, and the effect was devastating for the “Ambersons” auteur: “They destroyed ‘Ambersons,’ and it destroyed me.”

Nor was Welles the only one who was crushed. Herrmann threatened a lawsuit if his name was not removed from the credits after his score was shredded. (The film soundtrack is a mix of Herrmann’s work, that of Roy Webb and other music.)

With the excised footage destroyed and the rough cut lost, Welles considered reshooting the ending in the 1970s with the surviving cast members, but financing fell through. Yet ironically, whatever story Welles was trying to tell still shines. Though the film was a box-office disappointment in its day, it received an Academy Award nomination for Best Picture. The Library of Congress has selected it for its National Film Registry, and it has appeared on Sight & Sound magazine’s lists of top-10 movies.

And while the 2002 A&E remake has its pleasures – a scene of the Ambersons dancing in the snow, Jonathan Rhys Meyers as the obnoxious but ultimately courageous George – it can’t compare to the original.

So you see, like Eugene, Welles was true at last to his true love.