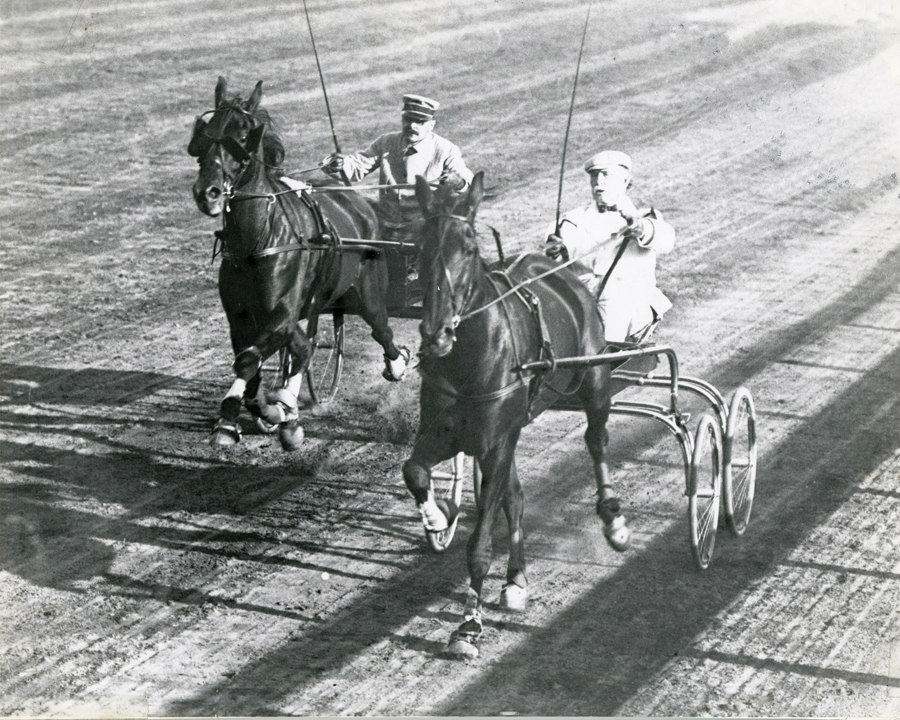

With its magnificent animals, highly skilled riders and intense international competition, show jumping enjoys its place as one of the most popular and most recognizable equestrian events.

At its highest levels, the sport is breathtakingly beautiful and a thrill to behold but also presents certain dangers to horses and riders. The United States Equestrian Federation has said that what pole vaulting, high jump and hurdles are to track and field, show jumping is to equestrian sport.

Each year, some riders experience falls that lead to injuries of varying degrees, none more serious than those that affect the brain and spinal cord, as we have seen in the cases of three riders with strong ties to Westchester County’s horse country. Actor Christopher Reeve, philanthropist Anne Heyman and Debby Malloy Winkler – daughter of Vivien Malloy, two-time New York Thoroughbred Breeder of the Year – all suffered falls while riding that ultimately led to their deaths.

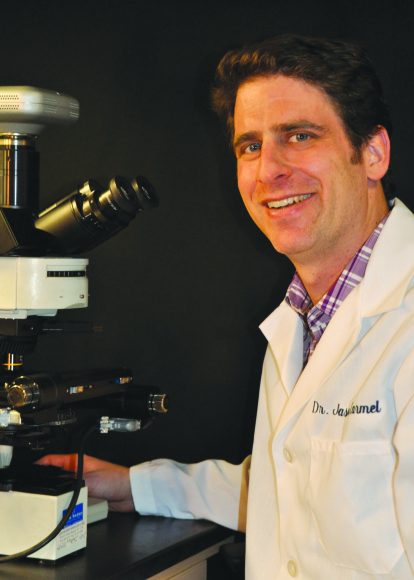

Two Westchester researchers – Richard Zeman, a scientist in the cell biology department at New York Medical College in Valhalla, and Dr. Jason B. Carmel, director of the Motor Recovery Laboratory at the Burke Medical Research Institute in White Plains – are conducting studies they hope will eventually help victims of serious spinal cord injury regain their mobility. But their approaches are quite different. Zeman is working with stem cells and drugs; Carmel, who specializes in electrical stimulation, also works with patients to retrain their bodies after spinal cord damage.

Brain to body

The spinal cord carries nerve fibers traveling both from the brain to the rest of the body and from the body back to the brain. Those impulses coming from the brain are responsible for the voluntary control of muscles. Those traveling toward the brain carry sensation.

In recent years, stem cell research has raised the possibility of repairing spinal cord damage. Zeman says he is working in his laboratory on injecting stem cells from the nervous systems of adult rats into the spinal columns of others that have been injured, “My stem cell work is still in the animal stage,” he says. “I am using stem cells plus an anti-inflammatory agent. The combination of the two appears to produce a beneficial effect in reversing paralysis.”

Zeman says there is a lot of promise in stem cell research. “But the spinal cord is extremely complex,” he added. “Stem cells can be transplanted into the spinal cords of rats and it has worked, but physicians have done this type of trial with humans on an extremely limited and very cautious basis. Some stem cell injections cause pain that can’t be treated, which is a very big concern. Other problems can also arise.”

Aside from stem cell research, he has found the testing of drugs like clenbuterol, which build muscle lost to paralysis, to be a promising avenue for spinal cord injuries.

“Using lab animals with injuries, we administer clenbuterol and determine how well they recover. We have found the drug to be potent in reducing muscle atrophy. We have also found that it prevents the loss of the spinal cord tissues themselves, and on average see an improvement in locomotor function.”

Zeman’s research also includes success in using clenbuterol as an anti-inflammatory agent on spinal tissues. And clenbuterol has yet another use: “When the spinal cord is injured, blood circulation is impaired,” he says. “We have found that when animals receive an injection of clenbuterol, blood circulation improved significantly. Loss of blood flow causes tissue to die, so finding a way to restore it on a permanent basis is very important.”

Administration of antioxidants also spares spinal cord tissue as does X-radiation. “We irradiated the rats and saw an improvement in the injured portion of the spinal cord,” he says. “We target the radiation to the spinal cord very carefully to get the best results. A few human patients have received this X-radiation therapy and there is a plan to begin clinical trials in the future.”

Zeman says he believes the combination of treatments he is exploring will yield results. “All of these things taken together give hope that, stem cell research aside, there are other effective ways to help patients with serious spinal cord injuries.”

Getting patients moving again

Meanwhile, at the Burke Medical Research Institute, Carmel conducts research on the repair of spinal cord injuries as director of its Motor Recovery Laboratory.

Independent studies have shown that about half are from motor vehicle accidents while the other half result from sports, falls and gunshot wounds.

“About 50 percent of the patients we see have some function, but the others have no residual function. At Burke, we have 16 different laboratories that focus on different aspects of nerve injury and repair. Our goal is to repair the brain and spinal cord so that we can restore as much function as possible.”

Carmel had a personal experience with spinal cord injury in 1999, when his twin brother suffered a serious injury that left him partially paralyzed. “Now we are seeing the fruits of the decades of research since then.

“In my laboratory at Burke, we study recovery of motor function after injury to the brain and spinal cord. Paralysis is caused when the connections between the brain and the spinal cord beyond the injury site are disconnected. We attempt to repair brain-spinal cord connections using activity-based therapies, including electrical stimulation and motor training.

“We have found that rats with injury and electrical stimulation fully recover walking, while those with injury only do not. We find that electrical stimulation acts like a Miracle-Gro for the nerve fibers in the spinal cord, causing them to sprout and form functional connections.”

Burke is a rehabilitation center with both a hospital and a research institute. In the hospital, Carmel said a large part of the work involves teaching patients how to make do with the function they are left with after injury.

“We teach everything from wheelchair use to catheterization to proper breathing techniques. Increasingly, the interventions target recovery of function and not just making do with limited movement. We use an array of different methods to help patients get function back. Paralyzed limbs can actually be trained to work again.”

After first pursuing an M.D. at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, Carmel decided also to obtain a Ph.D. at Rutgers University with the aim of devising a better treatment for spinal cord injuries.

Carmel says there are many nuances to spinal cord stimulation. “We believe that this promising therapy will be most successful if we know the proper timing, intensity and duration of the therapy. We are testing combinations of brain and spinal cord stimulation. I believe that my research will help us design safe and effective treatments for people with spinal cord injury.”