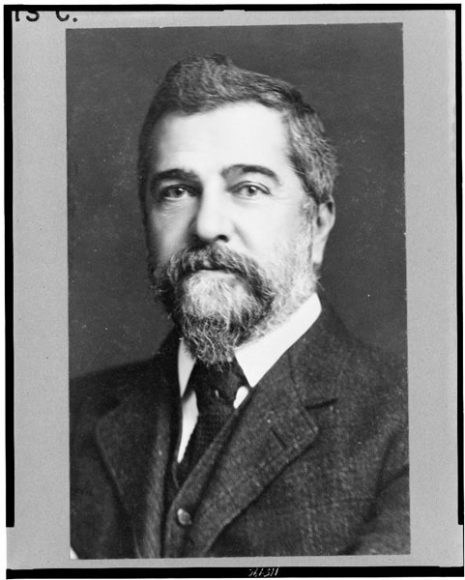

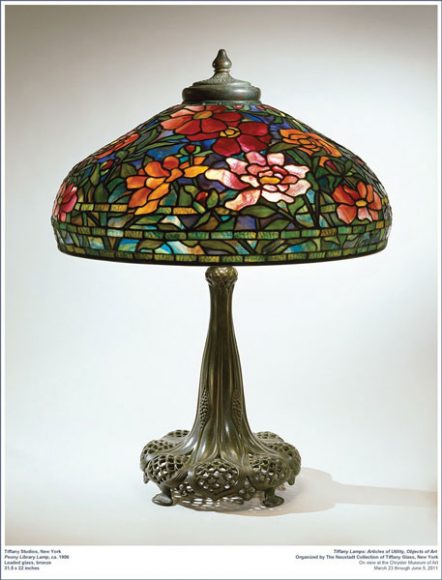

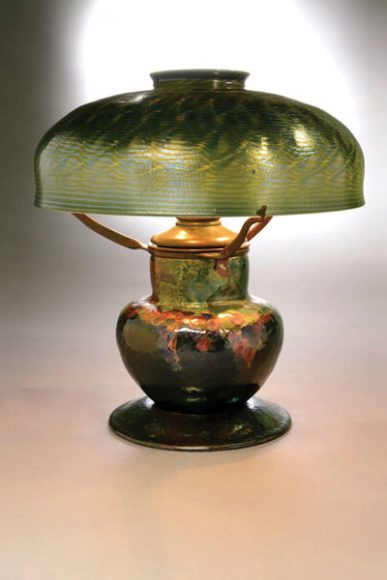

A mention of the name Louis Comfort Tiffany will most often draw to mind intricately crafted tabletop lamps or elaborately detailed stained-glass windows.

These decorative elements that have been coveted for decades are what Tiffany (1848-1933) is perhaps best known for.

But this summer’s exhibition at Lyndhurst in Tarrytown sheds new light on his legacy, crafting a well-rounded examination of Tiffany as an artist of varied talents.

“Becoming Tiffany: From Hudson Valley Painter to Gilded Age Tastemaker,” in both the Lyndhurst mansion and its gallery, takes visitors on a journey that focuses on the development of Tiffany’s career from the 1870s through the early 1900s.

“We are not a Tiffany-focused museum or institution,” says Howard Zar, the executive director of Lyndhurst.

But the exhibition and its subject have drawn elements from Lyndhurst, a National Trust for Historic Preservation site, and around the world. Lyndhurst notes there are more than 50 works, with a focus on creations both early and rarely exhibited, include glass and mosaics from the Haworth Collection in Accrington, England, the hometown of Tiffany’s glass foreman; rare textiles from the Mark Twain House in Hartford, for which Tiffany created designs; rarely seen early paintings from the Brooklyn and Nassau County art museums; and furniture and decorative arts from the Driehaus and other notable private collections.

“This is a really rare opportunity to see these things,” Zar says. After the exhibition, he adds, “These things are likely going back to storage for your life — and their life.”

Prompting the exhibition, Zar explains, was Lyndhurst’s strong connection to Tiffany, a longtime Irvington neighbor to Lyndhurst’s Gould family, and the growing knowledge of how Helen Gould, elder daughter of railroad magnate Jay Gould, was a significant Tiffany patron.

“We had been getting documentation from descendants of the Goulds,” Zar says, which helped frame the exhibition.

A NEW SPOTLIGHT

Tiffany’s lifelong work as an artist is not widely known, Zar says.

“I think one of the things that’s interesting to me is when we tell people, ‘We got his paintings,’ they say, ‘Whose paintings?’”

“Becoming Tiffany” indeed explores how the son of the founder of Tiffany & Co. used his family’s position and connections to carve out his own career, first as a painter and then in the decorative arts (though he would paint throughout his life).

It traces Tiffany from his days as a daring Hudson Valley painter — one whose themes and techniques challenged the norms of the day — to his worldwide travels that would influence his work at every step.

As Zar takes us through the exhibition, he points to the selection of paintings.

“This is art,” Zar says. The rest of the work, he notes, “was commerce.”

The Tiffany paintings, from “Pushing Off the Boat at Sea Bright, New Jersey” (1887) to the undated “Caravan Tents Before Village,” trace Tiffany’s unique approach in both technique and subject matter.

“He’s not painting the Gilded Age. He’s looking for ‘real life,’” says Roberta A. Mayer, professor emerita, art history, Bucks County Community College, who offered a lecture on “Louis C. Tiffany: ‘A Young and Promising Artist’” during the “Becoming Tiffany” symposium held June 3 at Lyndhurst.

Tiffany, as the exhibition follows, would explore racial inequality, begin sacred commissions with the Jewish community, comment on industrialization, introduce Orientalist subjects based on his travels and more.

It was only when Tiffany had trouble finding a market for his challenging work that he then transitioned into decorative goods, first becoming a partner in Associate Artists with Lockwood de Forest and Candace Wheeler.

“It gives a sense of the whole period and how these people interacted,” Zar says of the works of other artists featured in the show, with scene setters including a stunning carp-themed Wheeler fabric from the Mark Twain House and an elaborately carved de Forest table.

Throughout the exhibition, which does include the more familiar Tiffany lamps, vases, windows and more, the connection to the Goulds is also reinforced. Photographs, catalogs and inventories recently received from Gould family descendants helped establish the family as consistent and early purchasers of Tiffany’s works. Jay Gould, for example, commissioned an early Tiffany window for the Gould family mausoleum at Woodlawn Cemetery, while the exhibition’s concluding section focuses on philanthropist Helen Gould’s important Tiffany commissions for churches and libraries, including an early turtleback tile sconce from the recently restored Irvington Public Library.

In addition to works displayed in the Lyndhurst exhibition gallery, Tiffany lamps are exhibited in the rooms of Lyndhurst mansion to recreate those purchased by Helen Gould.

It all adds up to a new examination of a most familiar name.

As Zar says of “Becoming Tiffany,” which continues through Sept. 24, “This is a once-in-a-lifetime experience.”

For more, visit Lyndhurst.org.