“Mostly, we authors must repeat ourselves — that’s the truth. We have two or three great and moving experiences in our lives — experiences so great and moving that it doesn’t seem at the time that anyone else has been so caught up and pounded and dazzled and astonished and beaten and broken and rescued and illuminated and rewarded and humbled in just that way ever before.

Then we learn our trade, well or less well, and we tell our two or three stories – each time in a new disguise – maybe ten times, maybe a hundred, as long as people will listen….”

— F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “One Hundred False Starts: Twice Told Tales”

Scott Fitzgerald stood at the end of the dock of the imagination where he conjured tales of the unattainable American dream and the elusive women who often embodied it. This was never truer than in “The Great Gatsby,” his seminal 1925 masterwork — routinely acclaimed as one of America’s greatest and most popular novels — about a poor boy turned soldier and successful bootlegger who fatally amasses legendary wealth and fame, all for a first love whose virtues and vulnerability exist mostly in his mind.

Those of us who have read the book in school — or who are acquainted with any of several movie versions — are familiar with its crucial New York locales, including The Plaza hotel in Manhattan and the ash heap that was subsequently the sites of the 1939 and ’64 World’s Fairs and is today the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center in Queens.

Fitzgerald scholars have long thought Jay Gatsby’s over-the-top mansion to be situated on Long Island. (He wrote the book while living in Great Neck.) But what if his time in Westport — then a blend of struggling farmers, artists and new money —were an equal inspiration?

That’s the premise of a new book and documentary. Richard Webb Jr.’s “Boats Against the Current: The Honeymoon Summer of Scott and Zelda” (Prospecta Press, $40, 178 pages), the companion to Williams’ film “Gatsby in Connecticut: The Untold Story,” explores the five months Fitzgerald and his bride, Zelda, spent writing and (mostly) partying in the spring and summer of 1920 at a modest gray house on Compo Beach Road in Westport — and the influence this had on “Gatsby.”

“Some 200 pages of (Fitzgerald’s 1922 novel) ‘The Beautiful and Damned’ feature Westport to such a degree that you can walk through the town, using the book as a map,” says Webb, a Westport historian who grew up on Compo Beach Road near the Fitzgerald house. “The Beautiful and Damned,” he adds, is often considered a forerunner to “The Great Gatsby.”

Then there was the 1996 New Yorker article by Westport writer Barbara Probst Solomon, who connected the dots, particularly between Gatsby and Frederick E. Lewis II, the wealthy Tarrytown-born adventurer, explorer, inventor and sportsman who threw cinematic parties at Longshore, his 175-acre estate on Compo Beach Road — now a public country club and park — which was separated by a hedge from the Fitzgerald home.

Among those in ice cream-colored clothes who wandered Lewis’ ivy-covered terraces, perched beneath umbrella-ed tables and strolled past pools studded with water lilies were ballerina Anna Pavlova, Broadway impresario David Belasco, actresses Ina Claire and Marie Dressler, magician Harry Houdini, Connecticut Gov. Marcus Holcomb and, on one occasion, Zelda Fitzgerald, whom Lewis asked to leave. That was the story of Zelda’s life. Beautiful, self-indulgent and exhibitionistic, the spoiled Southern belle turned international flapper was always getting kicked out of some place with her hubby, mostly for their alcohol-fueled antics. (It was their exile from the Commodore Hotel in Manhattan, now the Grand Hyatt New York, that led them to Westport.)

No one could deny, however, that Zelda was a compelling figure, one who offered, along with her diary entries, continual inspiration to her husband’s work.

“They were America’s first rock stars,” Webb says. “They were actually pioneers of celebrity.”

Though Lewis kicked Zelda out of his party, the much-married tycoon continued to allow the socialite, who had a predilection for skinny dipping, to use his private beach.

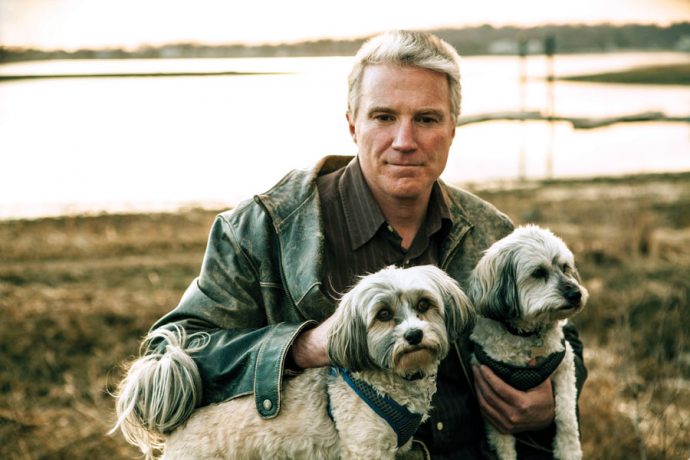

“He could see Zelda from one of his windows,” says Williams, a Westport filmmaker, author and musician, who met Webb at a 2013 Westport Historical Society panel discussion on the town’s great writers, which launched them on what Webb calls their “epic journey.”

“While there’s no mention of F. E. Lewis in their diaries,” Williams adds, “their house was next to the 175-acre estate. There were no other houses around.”

It doesn’t take much, then, to imagine Zelda bringing tales home to the Fitzgeralds’ more modest dwelling. Their parties were less lavish than Lewis’ but no less unmistakable.

Flush with cash from the sale of Fitzgerald’s first novel, “This Side of Paradise” — his income ballooned from $800 to $18,000 (about $235,000 today) in an era when people averaged less than $2,000 a year — Scott and Zelda let the good times roll.

“They had friends in from the city all the time,” Webb says. “Weekends started Thursday and ended Wednesday. One day they spent $500 ($6,500 today) on liquor. Food was rarely mentioned in their diaries. It was all booze….and orgies.”

The booze was bootleg, the Fitzgeralds’ move to Westport having coincided with the early days of Prohibition, and the orgies included key parties, in which the men put their keys in a bowl, and the women went off with the man attached to the keys they selected.

Such hedonism, the cut of the coastline, the elaborate Longshore parties and Lewis’ intriguing presence — even the names, Easton and Weston, Connecticut, possibly for East Egg and West Egg, Long Island in “Gatsby” — make a strong case for Westport as the prime inspiration for the novel. But some — like the late Fitzgerald scholar Matthew J. Bruccoli, who may have been protective of his own academic place — have dismissed the theory, shooting down Solomon’s original research and subsequent New Yorker article.

Williams and Webb were skeptical, too. “We asked people to disprove the theory,” Webb says, “but at every step people said, ‘No, you’re dead on.’” Besides Solomon, their supportive sources included Eleanor “Bobbie” Lanahan, a Fitzgerald granddaughter; Sam Waterston, who played “Gatsby” narrator Nick Carraway in the 1974 film starring Robert Redford; Charles Scribner III, grandson and namesake of “Gatsby’s” publisher; and actor Keir Dullea, who reads the Fitzgeralds’ words in the new documentary.

In the end, the story of “Gatsby” in Westport is really the story of the literary imagination’s ability to conflate experiences.

Germinated in Westport but incubated in Great Neck, “Gatsby,” Williams says, is “a beachy blend.”

Richard Webb Jr. and Robert Steven Williams will be appearing at Westport Library Oct. 10 and at the Union League Club in Manhattan Dec. 6. For more, visit gatsbyinct.com.