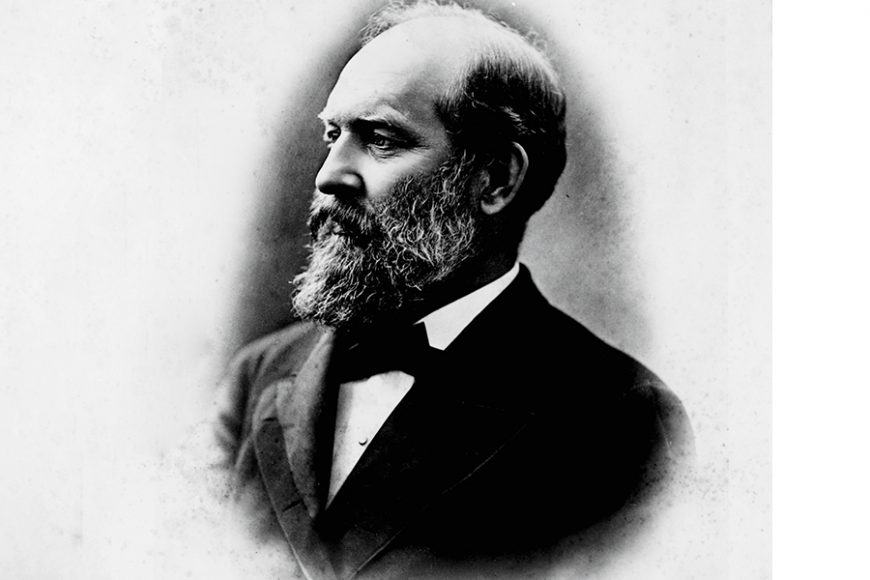

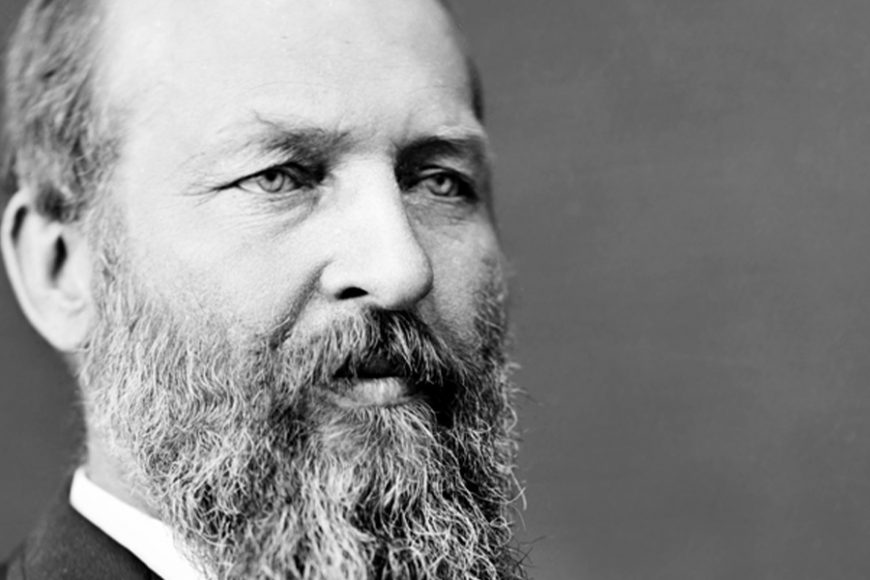

James Abram Garfield never intended to become the 20th President of the United States and, after his inauguration, he had little

opportunity to show his brand of leadership.

Today, Garfield mostly registers as a blip within the wider sweep of American history. But his life and death offer the story of a man who both shaped his era while falling victim to its limitations.

Garfield was born on Nov. 19, 1831, in a log cabin in Orange Township, Ohio. His childhood was heavy with challenges. His father died when he was 2, and he was raised in poverty by his mother. Garfield worked as a carpenter’s assistant and a janitor to finance his education and pursued careers as a teacher, lawyer and Republican state senator in Ohio before joining the Union Army in August 1861 with a colonel’s commission. His leadership at the Battle of Middle Creek in January 1862 resulted in a promotion to brigadier general.

Garfield was convinced by friends to seek the vacant seat for Ohio’s 19th Congressional District in 1862. He left the military for Congress and quickly became an influential political figure, backing civil rights for the freed slaves in the Southern states and the Gold Standard as the foundation of the U.S. currency. He showed no interest in higher office, although he was part of the Republican-majority commission that tilted the disputed Electoral

College votes in the 1876 election to Republican candidate Rutherford B. Hayes.

But Hayes — today judged an average president, despite his commitment to civil rights — had pledged not to seek a second term, and by 1880 the Republicans were in the hunt for a successor. Garfield arrived at the Republican presidential convention to nominate Treasury Secretary John Sherman but other factions were pushing for Sen. James G. Blaine of Maine and the return of former President Ulysses S. Grant. No candidate could secure a majority of support, and Garfield’s name was put forth to break the stalemate.

To Garfield’s utter horror, the convention delegates quickly warmed to having him as their standard bearer. By the 34th ballot, Garfield was within reach of gaining the nomination. He rose to address the convention, arguing, “I rise to a question of order. I challenge the correctness of the announcement. The announcement contains votes for me. No man has a right, without the consent of the person voted for, to announce that person’s name and vote for him in this convention. Such consent I have not given.”

The convention delegates ignored his protests and Garfield was selected as their nominee on the 36th ballot. “This honor comes to me unsought,” he lamented. “I have never had the Presidential fever, not even for a day.”

Garfield defeated his Democratic challenger, Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, by approximately 1,900 popular votes, the tightest margin in history. The electoral vote count was more lopsided, with Garfield polling 214 and Hancock 155.

Garfield was inaugurated on March 4, 1881 and almost immediately came to loathe the job. “My God! What is there in this place that a man should ever want to get into it?” he wrote in his diary. He would later confide to an aide, “My day is frittered away by the personal seeking of people, when it ought to be given to the great problems which concern the whole country.”

One of those people Garfield encountered was Charles Guiteau, a failed lawyer and writer dealing with mental illness. Guiteau was convinced that he was responsible for Garfield’s election and sought out a foreign service position from the new president. Garfield opted not to hire Guiteau, who began stalking the president’s forays into public.

Despite the Lincoln assassination of 1865, no one at the White House thought it was necessary to assign a security detail to the president. Garfield and his Secretary of State, James G. Blaine, walked by themselves from the White House to the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station in Washington on July 2, 1881, where the president was planning to take a train to the New Jersey seashore to visit his wife Lucretia, who was recovering from a bout of malaria. Guiteau trailed the men and fired two shots at close range from behind — one bullet grazed Garfield’s arm and the other passed the first lumbar vertebra of his spine and lodged in his abdomen.

“My God, what is this?” Garfield yelled as he fell to the floor. Guiteau, in his panic to escape, wound up running smack into a police officer at the station and was apprehended. The fallen Garfield was immediately attended by several physicians who were at the railroad station, including Charles Burleigh Purvis, an African-American and a co-founder of the medical school at Howard University.

However, another physician was summoned to handle the president’s care. Doctor Willard Bliss (his first name was Doctor), a childhood friend of Garfield, began examining the fallen leader on the train station floor by probing the wound with his unwashed fingers. Purvis openly questioned Bliss’ actions but was rebuffed — not because of racism, as Bliss was expelled from the Medical Society of the District of Columbia for denouncing its refusal to admit black doctors — but because Bliss did not embrace the then-controversial theory of antiseptic medicine that was being popularized by British surgeon Joseph Lister.

Garfield was returned to the White House and, over the next two months, Bliss would conduct multiple efforts to locate the lodged bullet using his unwashed hands and unsterilized equipment. Alexander Graham Bell was brought in with a metal detection device, but it failed to pinpoint the bullet’s location. Bliss widened the three-inch deep bullet wound to 20 inches, carving open Garfield from his ribs and to his groin. And while Bliss was aware of the increased levels of pus within the wound, he assumed it was evidence that the body was healing itself.

Throughout the ordeal, Garfield was bedridden and unable to consume solid food. His robust 210-pound frame withered to 130 pounds and the affairs of the Executive Branch were put on indefinite hold as the president suffered through fevers, chills and excruciating pain. The blistering heat of the Washington summer did not help, and on Sept. 5 Garfield was moved to the New Jersey location where his wife recuperated. But Garfield’s condition worsened into a bout of pneumonia and he complained of chest pains. On Sept. 19, Garfield passed, two months shy of his 50th birthday.

In the aftermath of Garfield’s death, Bliss submitted a claim to the federal government for $25,000 for his services. He was offered only $6,500, which he rejected. Guiteau was brought to trial and blamed Garfield’s death on medical malpractice rather than his gunshots. He was found guilty and hanged on June 30, 1882. Parts of his brain are on display in a jar at The Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

Garfield’s vice president, Chester A. Arthur, was sworn in as president after Garfield’s death. Their working relation was often testy before Garfield was assassinated, but Arthur made no effort to assume the presidential authority. There was no precedent on how the nation would be governed when the head of state became incapacitated. That issue would remain unresolved until the passage of the 25th Amendment to the Constitution in 1967.

Despite the assassinations of two presidents within 16 years, the concept of a security detail to guard the president would only become reality after the 1901 assassination of President William McKinley.

The Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station was demolished in 1908. The West Building of the National Gallery of Art is located at the station’s former site. Two temporary panels identifying the history of the site were installed in November 2018 just south of the West Building, but they are scheduled to be removed on July 2, 2021. Garfield remains the only slain president whose assassination site is without an official memorial.

Nevertheless, his life — and particularly his death — helped define the presidency he was so reluctant to assume.

For more, visit the James A. Garfield National Historic Site at nps.gov/jaga/index.htm.